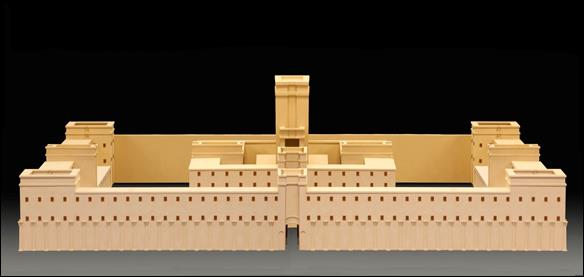

The architectural model of Newton’s Temple of Solomon

Through an Australian Research Council Post-Doctorial Fellowship, Babson Ms 434 was translated, its relationship with other manuscripts analysed and a recreation of the Temple using Newton’s written reconstruction using the 3D computer modelling program, ArchiCad, was carried out. An architectural model of the Temple was built from that computer model in 2011 (see Figure 7, 8 and 9). The model was built at the Architecture and Built Environment Workshop, the University of Newcastle, Australia, by Ben Percy and the Author. It was constructed with architectural modelling lasermachines and involved fused deposition modeling,an additive manufacturing technology which is commonly used for modelling, prototyping, and production applications. The materials used included MDF and ABS plastic. There are 1000 columns and 1200 window grids and it took over nine months to build. The scale of the model is 2.2 metres x 2.2 metres. It is constructed exactly to Newton’s description.

The difference between the models built from Villalpando’s and Newton’s reconstructions is significant. Apart from the corner towers and the symmetry there are no details that are similar. Although it is not known whether Newton saw the Schott model, even though he was living in London for the first three years it was exhibited, he would not have approved of the design of the model. In Babson Ms 434 Newton is highly critical of Villalpando’s reconstruction in In Ezechielem Explanationes.

Figure 7: Architectural model constructed by the author from Newton’s description in Babson MS 434

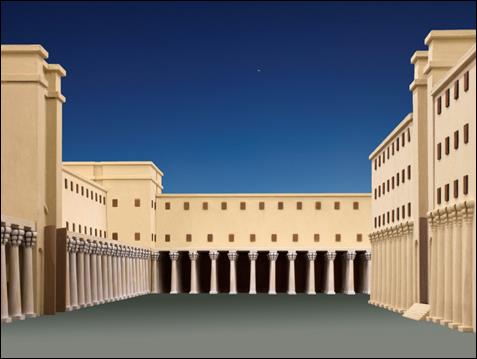

Figure 8: The single colonnades that surround the outer courtyard of Newton’s Temple of Solomon (from author’s construction)

He believed that Villalpando’s errors in his design were primarily derived from his failure to take advantage of Jewish sources and his misinterpretation of the Latin texts (Newton, c1680s, 32r). Newton pointed to the Latin text that Villalpando used sometimes differed in its translation to the Hebrew texts, for instance in the Latin version in Ezekiel 42:3 Villalpando translated ‘colonnades united’ to be a triple colonnade but in the Hebrew text it translated to ‘colonnade against colonnade three times’ indicating three storeys (Newton, 2011, 117).

According to Newton, Villalpando created his grid plan of the Temple precinct from an “incorrect translation’ and his plan “has no support and is lacking in reason” (Newton, 2011, 154). Villalpando interpreted Ezekiel 40:19-20 as meaning that the length of the atrium from the south to the north is the distance between the gates, a hundred cubits, and this divided the area of the precinct into nine small atriums or anterooms, two of which formed the temple atrium and seven exterior to it. These anterooms are divided from each other by triple colonnades fifty cubits wide. Newton pointed out that these anterooms not mentioned in Ezekiel. Regarding the thirty chambers that flank the sides of the gate, which are expressly mentioned by Ezekiel, it is impossible to arrive at the number 30 for these chambers if the spaces of the gates are not counted. However, this goes against the text of Ezekiel. In addition, Newton also claimed that Villalpando’s grid plan cannot be accepted “unless we want to move away from the proportion of Moses’ atrium that surrounds the immediate Temple and the altar, which was established by Villalpando himself as being a length over double its width (Newton, 2011, 153).” By putting in nine small atriums, Villalpando had made Temple Precinct 100 x 250 cubits instead of double square of 100 by 200 cubits prescribed by Moses.

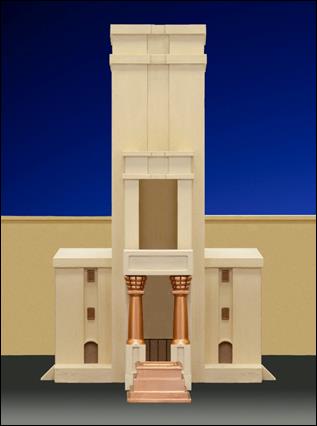

Figure 9: The outer courtyard between the gates (from author’s construction)

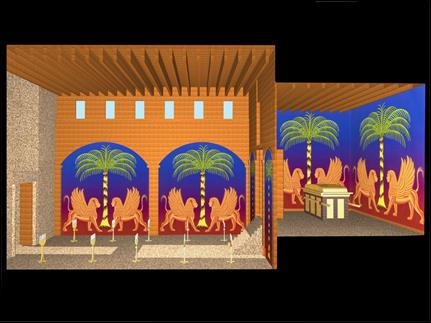

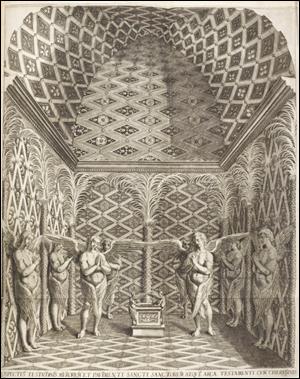

Although Newton’s reconstruction is classical in its nature, it is by no means ornate. Simplicity and harmonious design is central to his description. So are the measurements and the proportions. All of the measurements are in ratios of 1:2. 1:3 and 2:3. Not only is Newton’s design different to Villalpando in its exterior architecture it is also different internally. Inside the Temple (Figure 11) it is decorated with cherubim, which have a body of the lion and two faces. Newton clearly states that the temple

was decorated with Cherubim and palm trees. The palm trees were between the cherubim, and all the cherubim had two faces. So that there was a face of man towards the palm tree on the one hand and a face of lion next to the palm tree on the other side, throughout the house on every side (Newton, 2011, 141).

Newton kept to Ezekiel’s text and the Holy of Holies is described as being 20 x 20 cubits in size. In I Kings 6:20 it is described as a cube 20 x 20 x 20 cubits but that description is not taken up by Ezekiel; however, although there is no detail of the ceiling there are floors above and the height of the entire Temple is 30 cubits with the raise of 12 steps to the Holy of Holies the height would be approximately 20 cubits in height with a flat roof.

This is unlike the haunting and mysterious interior of the holy of holies by Villalpando (Figure 12); it contains the Ark of the Covenant and the Cherubim that guard it. The Ark is not of the Biblical dimensions and Cherubim are more human and serene than the Biblical cherubim guardians, and Villalpando’s ceiling and its external roof of the Holy of Holies has no Biblical precedent (Villalpando and Prado, 1604: vol 2, 88). In many ways Villalpando’s internal description of the Temple contradicts Ezekiel’s text. The contrast between the two architectural models built to the description of Villalpando and Newton differ in almost all aspects.

Figure 10: the Temple and the altar in the secret precinct (from author’s construction)

Figure 11: Section of the Newton’s Temple and the holy area where the Arc of the Covenant is kept (from author’s construction)

Figure 12: Villalpando’s Holy of Holies the Temple and containing the Arc of the Covenant with kind permission from the British library

Conclusion

Villalpando’s ‘architecture of theology’ was a significant study of the 17th and early 18th century which stimulated debate that endured for 150 years. This debate was taken up by not only theologians but also architects, the scientific community, and the public. There is no doubt that the religious interest was a stimulus for this debate; however, the debate itself was on the architect of the Temple – not the architecture of the actual building nor theology itself. The architectural norms of the building of the Temple were to be a model for all architecture. For Villalpando, the Temple of Solomon was at the origins of architecture. Villalpando claimed that “Sacred architecture constitutes the origin of architecture, and the profane one is like a copy, or better still, as a shadow of sacred architecture (Villalpando and Prado, 1604, 414)”. Newton studied Vitruvius to work on his reconstruction, he was familiar with the text and he had no other manuscripts which required a study of the architectural norms. The architecture was an important aspect of his Temple reconstruction. Although he never stated that it is the origin of architecture, Newton confidently stated that, “I meet no mention of sumptuous Temples before the days of Solomon (Newton, 1988, 221)”. In the 18th century, in an unpublished manuscript, antiquarian William Stukeley argued that at the Temple of Solomon was the origin of architecture (Stukeley, 1721-24). In 1741, Bath architect John Wood in a book entitled The Origin of Building or the Plagiarism of the Heathens Detected clearly stated that the Temple was the origin of all architecture. The debate was wide and controversial; nevertheless, it did involve some of the most significant architects and scientists in this period.

Both Leon’s and the Schott model were part of that debate. Although the models had caught the imagination of the public when Leon was planning to come to England his introduction letters were to high ranking men of the church, scientific community, and architecture; when the Schott model arrived in England the public discussion was that the King would be purchasing it not for his own collection but for one of the universities.

The importance of the architecture is also promulgated in the guidebooks that was sold at the exhibitions. The guidebooks ‘walked’ the viewer around the Temple exploring the sacred spaces, and the architecture. What happened to the Lyon model after the exhibition in the 17th century is unknown; however, a relative Moses De Castro exhibited the model again 1759 to 1760 in London and Leon’s Hebrew guidebook was also later translated into English (Leon, 1776). Although by this time the academic interest in the architecture of Solomon’s Temple was wanning, the public interest remained.

Babson Ms 434 remained in manuscript form and his only published work on Solomon’s Temple was in The Chronology, posthumously published in 1728, which did not make any serious impact into the debate particularly since it did not describe any architecture and the ground plans which were provided were not from the hand of Newton. The reconstruction in The Chronology bears no resemblance to Babson Ms 434 (Morrison: 2013).

The model built in 2011 to Newton’s description of the Temple has been exhibited at The University Gallery, at the University of Newcastle, and at The SciTech Library at the University of Sydney. It attracted many visitors as well as regional and national media coverage and it continues to bring in viewers to see our exhibitors in regional galleries around New South Wales. There is a fascination with the reconstruction of the Temple by one of the greatest scientists that ever lived. It does appear from a 21st century point of view a strange study for such a significant figure in history to study. However, in his reconstruction Newton was contributing to an important ongoing and contemporary academic debate.

He believed that Villalpando’s errors in his design were primarily derived from his failure to take advantage of Jewish sources and his misinterpretation of the Latin texts (Newton, c1680s, 32r). Newton pointed to the Latin text that Villalpando used sometimes differed in its translation to the Hebrew texts, for instance in the Latin version in Ezekiel 42:3 Villalpando translated ‘colonnades united’ to be a triple colonnade but in the Hebrew text it translated to ‘colonnade against colonnade three times’ indicating three storeys (Newton, 2011, 117). He believed that Villalpando’s errors in his design were primarily derived from his failure to take advantage of Jewish sources and his misinterpretation of the Latin texts (Newton, c1680s, 32r). Newton pointed to the Latin text that Villalpando used sometimes differed in its translation to the Hebrew texts, for instance in the Latin version in Ezekiel 42:3 Villalpando translated ‘colonnades united’ to be a triple colonnade but in the Hebrew text it translated as ‘colonnade against colonnade three times’ indicating three storeys (Newton, 2011, 117).

[i]

Vitruvius, III, iii, 6. Eustyle is a type of temple whose columns had the better proportions according to Vitruvius, from the point of view of the aesthetics and of solidity. The length of its intercolumnios equalled to two diameters and a fourth of the columns, except the head of the subsequent and previous part; that midal is three diameters.

Дата добавления: 2016-07-27; просмотров: 2473;