Chronology, the Temple and Manuscript Corrections

Newton continually ‘refined’ his studies on prophecy and chronology, and both topics included works on the Temple. As consequence of this manuscripts were copied out in full as they were being refined. However, it is notable that many of his studies on prophecy and chronology, were no longer attributed directly to ancient and contemporary sources, but were a combination of Biblical sources, unreferenced history, myths and previous work that had been summarised with notably fewer references (for example Newton:, c 1700; Newton: post 1700; Newton, c 1701 –2; Newton: after 1710). His study of the Temple and the cubit were no longer an individual study for its mathematics, architecture and theological perspectives that played a significant role in the prophecy of Daniel, Ezekiel and John the divine and the chronology of Kings, but became the background of the prophecies and a small insignificant chapter in his work on chronology. Solomon’s, Zerubbabel’s and Herod’s Temples are discussed in theological and historical terms; however, the architecture becomes reduced to the biblical measurements of the floor plans and contains no consideration of the buildings (see Newton: c1699; Newton: 1701-2; Newton: after 1710).

After Newton’s death, John Conduitt edited and published The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended, which Newton had been revising for publication at the time of his death. Chapter 5 of the Chronology is entitled ‘A Description of the Temple’ and it is barely 3000 words long. The majority of the chapter quotes straight from Ezekiel, with very little added by Newton. The bits that he does add are very strange, for instance “the cubit was about 21  , or almost 22 inches of the English foot (Newton: 1988, 332).” Considering that Newton was one of the greatest mathematicians who ever lived, such imprecision appears contrary to his nature. The little architectural detail that he does give does not make much sense. He claimed that

, or almost 22 inches of the English foot (Newton: 1988, 332).” Considering that Newton was one of the greatest mathematicians who ever lived, such imprecision appears contrary to his nature. The little architectural detail that he does give does not make much sense. He claimed that

The Porch of the Temple was 120 cubits high, and its length from south to north equalled the breadth of the House: the House was three stories high, which made the height of the Holy Place three times thirty cubits, and that of the Most Holy three times twenty: the upper rooms were treasure-chambers (Newton: 1988, 342)

This strange and confused stepped structure appears to have no precedents, Biblically or otherwise.

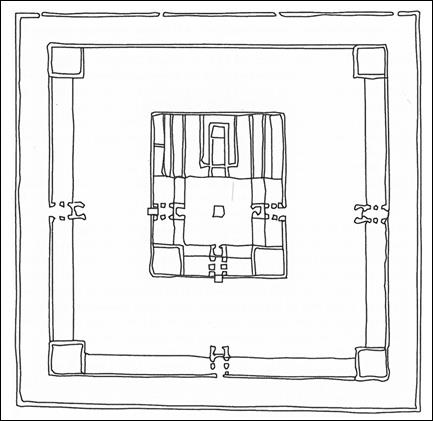

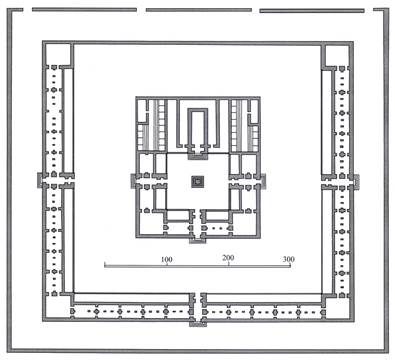

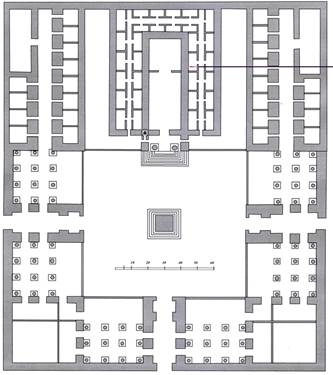

There are three very detailed plans accompanying the chapter but the detail in the plans is not backed up by description in the chapter. Although expertly drafted, the plans are a mixture of the details of Solomon’s Temple and the Zerubbabel’s Temple as described in the Bible.[iv] The final form of The Chronology, in Newton's best handwriting, with hardly any deletions or emendations, can be seen in a manuscript held at Cambridge University Library, Additional Ms 3988. However, the drawing that accompanies the text of this manuscript is a mixture of the two Temples, Solomon’s and Zerubbabel’s Temples, and the plan lacks any detail. It is the most minimal of plans, with no internal detail (See Figure 4). The crude outline of this plan is similar to the plan of the Temple precinct in The Chronology but it is extremely different to the one in Babson Ms 434. The draftsman of the plans in the Chronology may have had knowledge of this plan. But the three plans in The Chronology (see Figures 5, 6 and 7) should not be considered the work of Newton. The details in these three plans are a fabrication from an unknown hand.

In the Preface to a 1770 edition of The Chronology, which is in the form of a correspondence between Dr Thomas Hunt, Hebrew Professor at Oxford University and Rev Zachary Pearce, the Bishop of Rochester, Hunt claimed that after Newton’s death there had been sixteen drafts of The Chronology in Newton’s papers. The Bishop expressed his concerns about Newton’s methods of writing:

It is a pity, that he took so much of the same method in his chronology which he took in his Principia &c: concealing his proofs and leaving it to the sagacity of others to discover them. For want of these, in some instances what he says on chronology does not sufficiently appear at present to rest upon anything but his assertions;…But proofs he may have had, which he chose to conceal, though what now stands in the Margin in those few places may have come from another hand, and may not amount to a full proof, as it pretends to do (Pearce, 1770, 7-8).

William Whiston, claimed that Newton wrote out eighteen copies of The Chronology, but that they were not very different from each other (William:1749, 39). Only a couple of the later versions, which Whiston would have known about, still exist.

Newton had worked on chronology since his earliest days in Cambridge; it was a topic that he kept returning to. The final published version of The Chronology was a result of many manuscripts, but instead of improving it and building on his research, Newton made it blander and blander with each reworking, and his final drafts, which resulted in the published work, had none of the scholarship, uniqueness or the content of his earlier works. This is particularly demonstrated in his work on the Temple of Solomon. Manuscripts such as Babson Ms 434 and his work on the cubits, were the work of the middle-aged Newton in his most productive period of the 1680s and early 1690s that demonstrates the depth of his research.

Figure 4: Copy of the sketch by Newton in Additional Ms 3988 drawn by author

Figure 5: The floor plan of the Temple precinct published in the Chronology in 1728 (Drawn by author from (Newton: 1988, unpaginated).

Figure 6: The floor plan of the Temple and inner court published in the Chronology in 1728 (Drawn by author from (Newton: 1988, unpaginated).

Figure 7: Floor plan of the cloister under the chambers published in the Chronology in 1728 (Drawn by author from (Newton: 1988, unpaginated).

Conclusion

The study of Solomon’s Temple in the late 17th and early 18th century was not uncommon. Theologians and architects were making academic studies of the Temple, particularly in the wake of the Villalpando’s reconstruction. The public’s interest was frenetic in both Britain and Europe. In Britain the newspapers reported that King George I was considering purchasing the Schott model for £20,000 (Anonymous: 1724b, 2) the equivalent of $2 million. That sale did not go ahead but after the death of King George I it was reported that “We hear his majesty (King George II) has purchased the famous model of the Temple of Solomon brought from Hamburg in the last Reign, and shown at the Hay Market, to make a present of it to one of the universities (Anonymous: 1724a, 2).” This sale also did not go ahead and it continued to be displayed in London until it was purchased by Elector Friedrich August of Saxony, who was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania in 1732.

William Whiston, also gave public lectures on the Temple. However, he stated that Ezekiel’s vision was not of Solomon’s Temple.

As for Sir I.N’.[Isaac Newton’s] description of Solomon’s Temple; (I think he should call it Ezekiel’s Temple; for he takes it principally from Ezekiel, who describes neither Solomon’s, nor Zorebabels,’ nor Herod’s, but the Jews futureTemple) I reserve its examination till I publish my own plan of all those Temples (Whiston: 1727, 1070).

Unfortunately he did not publish his plan but he continued to lecture on the Temples of Jerusalem in clear opposition to the Schott model. However clearly he did not agree with his old mentor. In his advertisement for his lecture he distinguished between the Temples. Whiston lectured “upon sacred architecture past; of the models of the Tabernacle of Moses; of the Temples of Solomon, Zorobabel and Herod: And upon the sacred architecture future, of the model of Ezekiel’s Temple (Anonymous: 1724a, 2) stop” For Whiston, Ezekiel’s vision was a prophesy of the future and had not been built. Whiston lectured at Grigsby’s Coffee House, behind the Royal Exchange, on Wednesdays, and Button’s Coffee House in Covent Garden on Friday. However, as public interest increased by this time Newton’s interest had faded to a shadow of his early studies.

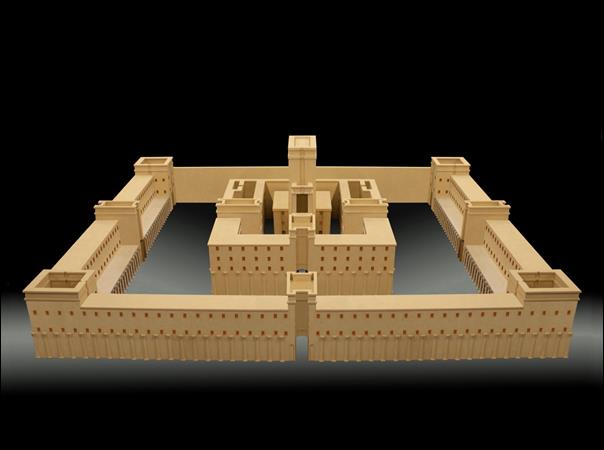

Newton’s study of the Temple is significant, Babson Ms 434 displays his understanding of architecture and architectural theory of the Roman theorist Vitruvius, and a wide range of ancient and contemporary sources. It was also a topic that was of contemporary interest. However, why Newton ‘refined’ his study to what became bland and architecturally nonsensical in Chapter 5 of the Chronology at the height of public interest in the Temple is unknown.

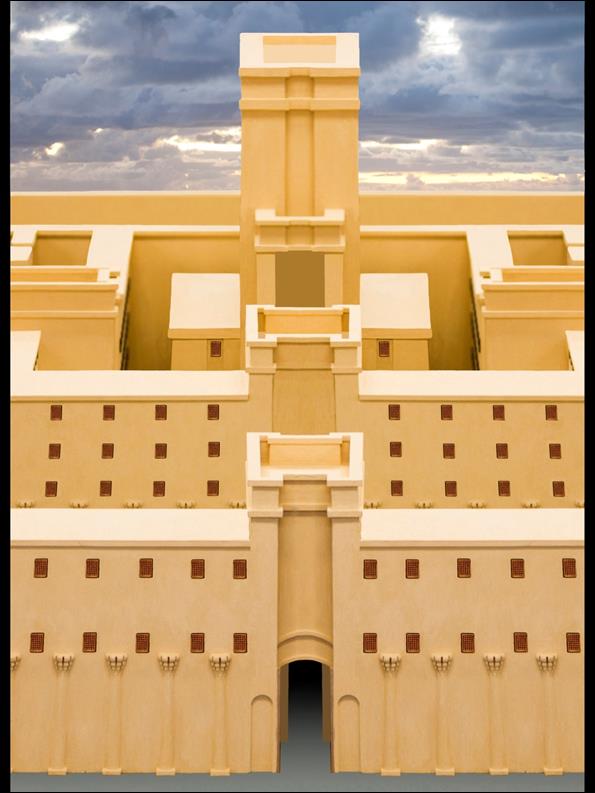

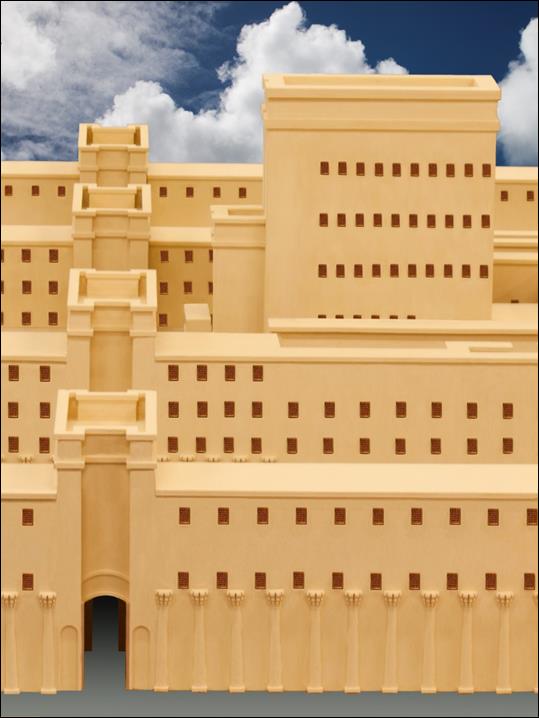

Figure 8: Architectural model of Newton’s Temple of Solomon as described in Babson Ms 434 the model is 2.2 m² and was built at the school of architecture and engineering’s workshop, the University of Newcastle, Australia

Figure 9: view of the Temple from the East

Figure 10: view of the Temple from the North

[i]

References for four-seven examples of these reconstructions are listed in (Herrmann: 1969).

[ii]

An example of this example can be seen in the Gale database ‘Eighteenth Century collection’ sourced from the British Library.

[iii]

The ‘Tractate Middot’ is the part of the Talmud that deals with the architecture of the Temple.

[iv]

In the floor plan of the Temple precinct in The Chronology an external wall encloses the entire precinct wall. This external wall has four gates on the Western side, which were the Gate of Shallecheth, the Gate of Parbar, and the two Gates of Assupim. This wall and the gates belong to the Second Temple (1 Chronicles 26:16–18).

Дата добавления: 2016-07-27; просмотров: 1797;