Principia Mathematica

The description of the Temple of Jerusalem in the Book of Ezekiel is dark and obscure. Not only are the details of the buildings that constitute the Temple precinct obscure, so are the answers to the questions: which Temple is it? – is it Solomon’s Temple? Is it the Temple that existed in Ezekiel’s time? Or is it the Temple of the future? In 1604, architect and Jesuit priest Juan Battista Villalpando published In Ezechielem Explanationes et Apparatus Vrbis Templi Hierosolymitani. This is a three volume commentary on the Book of Ezekiel; however, the entire second volume is dedicated to Solomon’s Temple and is based on Ezekiel’s description of the Temple. Villalpando reconstructed the Temple illustrating it with elaborate etchings. He claimed that his reconstruction was the ‘architecture of theology’ for the betterment of his fellow brethren. His reconstruction was extremely controversial and his work began a debate that endured for one hundred and fifty years. However, this debate is not just theological it was primarily architectural. Architects, theologians and Hebraists critiqued Villalpando’s reconstruction, often creating their own reconstructions. Some of these reconstructions remained on paper, while others were later turned into architectural models. Two models were displayed in London. The first model was by Jacob Judah Leon (Templo) exhibited in London from 1675, and the second Gerhard Schott’s model was exhibited in London from 1724 to 1732. Both models were extremely different and the reconstructions were built to different sources. However, Isaac Newton, who also reconstructed the Temple in a manuscript, would not have agreed with either of the exhibited reconstructions. This paper firstly considers the Leon and Scott models exhibited in London. Second, it will turn to Isaac Newton’s reconstruction and how it fits in with these publicly displayed models. Finally there will be a discussion of the new architectural model of Newton’s reconstruction and a comparison between it and Villalpando’s reconstruction

More Info:http://avellopublishing.wordpress.com/journal/

Publication Date:2013

Publication Name:Avello Publishing Journal

The description of the Temple of Jerusalem in the Book of Ezekiel is dark and obscure. Not only are the details of the buildings that constitute the Temple precinct obscure, so are the answers to the questions: which Temple is it? – is it Solomon’s Temple? Is it the Temple that existed in Ezekiel’s time? Or is it the Temple of the future? In 1604, architect and Jesuit priest Juan Battista Villalpando published In Ezechielem Explanationes et Apparatus Vrbis Templi Hierosolymitani. This is a three volume commentary on the Book of Ezekiel; however, the entire second volume is dedicated to Solomon’s Temple and is based on Ezekiel’s description of the Temple. Villalpando reconstructed the Temple illustrating it with elaborate etchings. He claimed that his reconstruction was the ‘architecture of theology’ for the betterment of his fellow brethren. His reconstruction was extremely controversial and his work began a debate that endured for one hundred and fifty years. However, this debate is not just theological it was primarily architectural. Architects, theologians and Hebraists critiqued Villalpando’s reconstruction, often creating their own reconstructions. Some of these reconstructions remained on paper, while others were later turned into architectural models. Two models were displayed in London. The first model was by Jacob Judah Leon (Templo) exhibited in London from 1675, and the second Gerhard Schott’s model was exhibited in London from 1724 to 1732. Both models were extremely different and the reconstructions were built to different sources. However, Isaac Newton, who also reconstructed the Temple in a manuscript, would not have agreed with either of the exhibited reconstructions. This paper firstly considers the Leon and Scott models exhibited in London. Second, it will turn to Isaac Newton’s reconstruction and how it fits in with these publicly displayed models. Finally there will be a discussion of the new architectural model of Newton’s reconstruction and a comparison between it and Villalpando’s reconstruction.

Background

Juan Battista Villalpando’s In Ezechielem Explanationes et Apparatus Vrbis Templi Hierosolymitani published in 1604 was more than a commentary on Ezekiel, it was over 20 years in the making and was financed by Philip II of Spain, who originally promised 3000 gold escudos for the engravings and other expenses (Taylor, 1972, 74). Eventually this amount rose to 10,000 gold escudos over the 20 year duration of the project. Villalpando claimed that

I have not studied it (the Ezekiel’s vision of the Temple) in order to re-establish the old glory of the Temple, but in order to interpret the text of the Scriptures that contain the sublime mysteries of our religion; my intention was to clarify everything that is the object of our sensorial comprehension of this information to discover other more defined elements (Villalpando & et al: 1604, unpaginated).

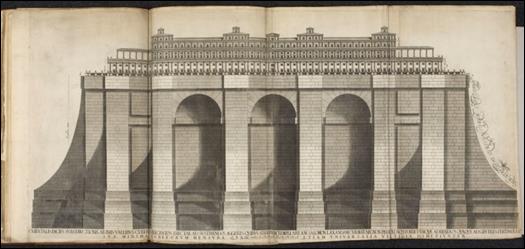

In order to “clarify everything that is the object of our sensorial comprehension” the book contains 48 copperplate engravings: 20 of these fold out with some being over one and half metres wide. These engravings are of exceptional quality, and reproduce the plans, elevations and perspectives that Villalpando believed were originally drawn by the divine hand of God. For Villalpando it was the ‘Architecture of Theology’, which revealed the mind and plans of God.

There was an overwhelming response to In Ezechielem Explanationes and its notoriety was spread through commentaries written by both supporters and critics. The first commentary, Annales Sacri by Agostino Tornielli, was published in 1610 in Milan and it was reprinted a further six times in Frankfurt, Antwerp and Cologne over the next 50 years. Louise Cappel made an extensive study of the Temple, which contains abstracts from In Ezechielem Explanationes and was printed in Brian Walton’s Biblia Sacra Polyglotta in 1657; this was revised in John Pearson’s Critici Sacri and published in 1660. Nicolaus Goldmann’s Architectura Sacra written before 1665, made Villalpando’s work known in Germany. Fisher von Erlach’s Entwurff einer Historischen Architectur included Villalpando’s Temple and was printed in Vienna in 1721. In Ezechielem Explanationes, with its high quality etchings the book was expensive and it was through these books, which contained abstracts and/or commentaries of Villalpando’s work, that it became widely known.

There were also reconstructions of the Temple in response to Villalpando’s reconstruction, such as architect Claude Perrault published The Code of Maimonides, the Mishneh Torah, in 1678; Hebraist Constantin L’Empereur’ published Mishnah sive Legum Mischnicarum liber qui inscribitur Ordo Scorum…., in 1702; architectural theorist Nicholaus Goldmann’s Die Vollstandige Amweisung zu der Civilbaukunst published in 1698; non-conformist minister and natural philosopher, Samuel Lee published Orbis miraculum, or, The temple of Solomon pourtraied by Scripture-light in 1659 with a second edition in 1665 and many more. Jesuit priest Benito Arias Montano published a reconstruction of the Temple in ‘Exemplar’ in Volume Eight of the Antwerp Polyglot in 1572 before Villalpando began work on his reconstruction in the early 1580s. Montano’s reconstruction was based on the description of the Temple from the Book of the King. He was the first to criticise Villalpando's work well before its publication and he accused Villalpando of heresy and challenged him for his controversial ideas; including using the Book of Ezekiel as his source for his reconstruction – although Villalpando was charged with heresy and had to face the Inquisition his case was eventually dropped.

There were also unpublished reconstructions such as Isaac Newton’s Prolegomena ad Lexici Propretici partem Secundam: De Forma Sanctuary Judaici (Babson Ms 434). Newton’s comments in Babson Ms 434 on Villalpando’s reconstruction are a mixture of both support and criticism. Whereas Newton praised Villalpando’s theological justification for his reconstruction, he was highly critical of his architectural reconstruction. In Babson Ms 434 he creates a reconstruction using the same principle source as Villalpando, the Book of Ezekiel and he justifys his reconstruction using ancient and contemporary sources (see (Morrison, 2013) for the sources used by Newton in Babson Ms 434.

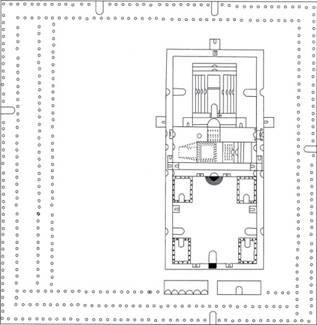

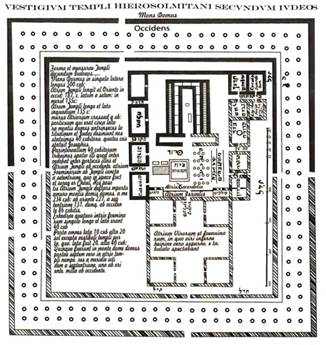

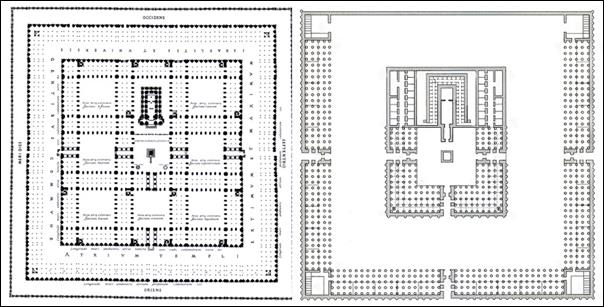

The reconstructions of Solomon’s Temple in the 17th and beginning of the 18th century show several variants. However, they did loosely divide into two basic designs – symmetrical and non-symmetrical. The main cause of this difference was the use of different literary sources. Ezekiel was ambiguous and open to interpretation; the main continuity between the reconstructions from the book of Ezekiel was symmetry, while in the traditional Jewish sources the accounts of the Temple were more specific and non-symmetrical (Shalev, 2003). Examples of the non-symmetrical plans by Constantin L’Empereur and Louis Cappel can be seen in the Figures 1 and 2, and both these plans were from Mishneh Torah. While Villalpando’s and Isaac Newton’s ground plan (see Figure 3) are symmetrical and based on Book of Ezekiel. In the plans based on Mishneh Torah there is a great deal of similarity, while the plans based on the book of Ezekiel although similar in their symmetry, their ground plans can vary greatly which can be seen between the plans of Villalpando and Newton.

Figure 1: Constantin L’Empereur’s floor plan of the Temple from Guglielmus Surenbusius;

Mishnah sive Legum Mischnicarum liber qui inscribitur Ordo Sacrorum…, 1702 (drawn by the Author from (Curl, 1991, 89)

Figure 2: Louis Cappel’s reconstruction of the Temple from Brian Walton’s Polyglot Bible published in 1657 (Cappel, 1657, 39)

Figure 3: left hand side – Villalpando’s floor plan of the Temple of Solomon (Drawn by the author from (Villalpando and Prado: 1604, unpaginated)); Right-hand side – Isaac Newton’s Plan of the Temple drawn from his description in Babson Ms 434.

Figure 4: Villalpando’s Temple of Solomon and its massive foundations, with kind permission from the British library

The Two London exhibitions in the 17th and 18th centuries

The interest in Solomon’s Temple was not just an academic one. Architectural models were built of these temples and displayed publicly. Although many models of Solomon’s Temple were publicly exhibited throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, there were two architectural models that captured the public’s imagination in this period – Jacob Judah Leon (Templo)’s model, exhibited in London from 1675, and the Gerhard Schott’s model which was exhibited in London between 1724 and 1732. Schott’s Model was built to Villalpando’s plan while the Leon model was built according to the Jewish sacred texts (see Figure 5), representing the two distinctly different plans of the Temple – symmetrical and non-symmetrical.

Both these models were large and at the exhibition the viewer could purchase a guidebook of the Temple. These guidebooks were descriptive walks through the Temple bringing the viewer into the Temple. Both models were extremely different in their overall design and in the details. However, they were both extremely popular public exhibitions.

Few men have had as many varying aliases as the Rabbi Jacob Judah Leon, Hebrew for Judah Arje, Aryeh or Arye, (in Continental Europe Leo, Leon Leonis or Leonituis,) and in England Lion or Lyon. A surname Templo was given to him by his contemporary scholar because of his life’s work on the Temple of Solomon and the models that he exhibited (Crawley and Chetwope, 1898, 153). However, Leon never used the surname of Templo himself. He signed himself in Hebrew lettering as Yacob Yehuda Aryeh and is referred to in his literary works as Leon Hebreo (Shane, 1983, 149).

Leon became a Rabbi and teacher for the Sephardi community and by 1642 he had completed a model of the Temple of Solomon and published Retrato del Templo de Selomoh in Spanish and Afbeeldinghe vanden Templel Salomonis in Dutch which was also translated into French, Portraict du Temple de Salomon. Throughout his life his work was translated into no less than eight languages, Dutch, Spanish, French, German, Hebrew Yiddish, Latin and English.

Leon’s exhibition was very popular with not only the pubic but also with Royalty and the scientific community. In 1642, Frederick Henry, the Stadtholder of the Provinces of Holland, visited the new synagogue in Amsterdam. He was accompanied by his son Prince William of Orange, Mary Stuart, who was Prince William’s betrothed, and her grandmother Queen Henrietta Maria. They also visited the Temple exhibition which was on display at Leon’s house. In his second edition of the Dutch edition Afbeeldinghe vanden Templel Salomonis Leon included two dedicatory poems. One is signed I. D Brune, who is thought to be the Christian poet and Hebraist Johan de Brunes the Elder (Shane, 1983, 151). Constantijn Huygen, secretary to the two Princes of Orange, Frederick Henry and William, and the first secretary to the Dutch Royal Society, was interested to support Leon’s work by writing him letters of introduction letters for his intended visit to London in 1675. This would have been an important contact for Leon and indicates the respect that the Dutch scientific community held for him.

Huygen’s introduction letters for Leon for his intended trip to England to exhibit his models were sent to Henry Bennet, 1st Earl of Arlington, Henry Oldenburg, the secretary of the Royal Society, and Christopher Wren. A copy of the letter sent to Christopher Wren is preserved in Koninklijke Bibliotheek, The Hague, and is dated 7th October 1674, and states that:.

This bearer is a Jew by birth and profession, and I am bound to him for some instructions I had from him, long ago, in the Hebrew literature. This maketh me grant him the addresses he desireth of me, his intention being to show in England a curious model of the Temple of Solomon, he had been about to contrive these many years, where he doth presume to have demonstrated and corrected an infinite number of errors and parallelisms of our most learned scholars, who had meddled with the exposition of that holy fabric, and most specially of the Jesuit Villalpando, who, as you know, Sir, has handled the matter ingenti cum fastu et apparatu, ut solent isti [with enormous display and complexity]. I make no question but many of your divines and other virtuois will take some pleasure to hear the Israelite discourse upon his architecture and the conformity of it with the genuine truth of the holy text, but, Sir before all, I have thought I was to bring him acquainted with yourself, who are able to judge of the matter upon better and surer grounds that any living man. I give him also letters to the Portuguese ambassador, to my lord Arlington and M, Oldenburg that some notice be taken of him, both at court, and amongst those of the Royal Society. If you will be so good as to him unto my lord Archbishop of Canterbury his Grace, even in my name, I am sure the noble prelate will take it pro more suo [according to the custom of men] friendly and remember with me the Psalm, Laetatus sum in his quae dicta sunt mihi, in domum domini ibimus [I rejoiced when they said to me, let us go into the house of the Lord]. I pray, Sir, let his Grace find here my humble and most devoted respect, and for your part I believe I do still remember your excellent merits, and in consideration of them and will always show to be (Worp, 1917, 274).

Дата добавления: 2016-07-27; просмотров: 2793;