Origin and development of geography. Early history

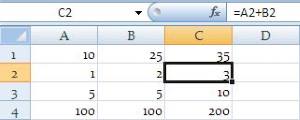

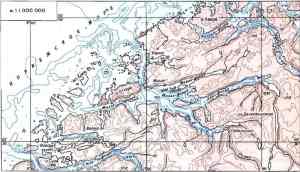

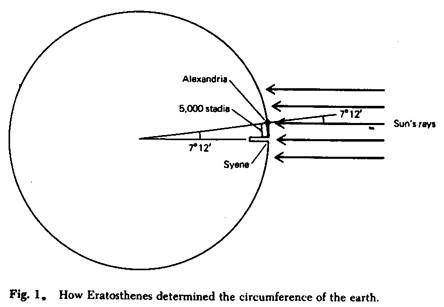

Human beings have always wondered how other lands and peoples differ from their own home and folk. The first recorded knowledge of such differences came mainly from the accounts of travellers1. The 5th century B.C. Greek writer Herodotus was an outstanding early example of one who carefully recorded his personal observations made during many years of extensive travel. The Greek perception2 of the Earth was highly advanced: the philosophers Pythagoras and Aristotle believed it to be a sphere3 and the Pythagorean Philolaus taught that it revolved around a central fire. In the 3rd century B.C. Eratosthenes of Cyrene, whose Geographica was the first work to have the word geography as its title, employed ingenious reasoning4 and measurements to produce a remarkably accurate calculation of the circumference of the Earth. He had observed that at Syene (modern Aswan, Egypt) at noon on the summer solstice5 the Sun was directly overhead, while at Alexandria it cast a shadow. By calculating the angle of the shadow and using the distance between Syene and Alexandria, Eratosthenes arrived at a figure of 250,000 stadia (or stades) for the Earth’s circumference (see Figure 1).

Eratosthenes’ figure, however, subsequently was rejected by classical geographers, such as Ptolemy – who calculated, erroneously, that the Earth was much smaller.

In his 17-volume work written at about the time of Christ, the Greek geographer and historian Strabo provided the most detailed summary and review of the classical knowledge of geography. the first two books were devoted to a wide-ranging discussion of the aims and methods of geography and to a review of earlier writings; many early works of Greek or Roman authors have disappeared or have survived only in fragments and they are known today only through Strabo’s critical comments in these books. The other 15 books written by Strabo provided regional descriptions. The great contribution of the 2nd century A.D. astronomer and geographer Ptolemy was the concept of the tabulation6 of latitude and longitude7 of places; these tabulations could give precision to locations, but Ptolemy’s data again contained errors8 that were to plague9 geographers for centuries.

With the breakup of the Roman Empire in the West, most of the geographic knowledge of the Greeks gradually was lost in Europe, but during the 11th and 12th centuries it was preserved, revised, and enlarged by Arab geographers. Geographic study in Europe was stimulated anew by contact with Muslim learning10 during the Crusades11, although in their reacquaintance with Greek ideas – particularly those of Ptolemy – European thinkers generally ignored the additions and corrections of the Arabs. Thus, the errors of Ptolemy were perpetuated in the West until the voyages of the 15th and 16th centuries started bringing back to Europe detailed and more accurate information of the rest of the world.

An important figure of the new learning was the German scholar Bernhardus Varenius (Bernhard Varen), whose Geographia Generalis (1650, General Geography) was revised numerous times and remained a standard reference work for a century or more. Unlike many earlier writers, Varenius included ideas based on direct observations and original measurements. In the century before Varenius, the Flemish cartographer Abraham Ortelius prepared a world map in sections and bound them together in book form in his Theatrum orbis terrarium (1570, Epitome12 of the Theatre of the World), the first atlas. The first use of the term atlas, however, was by Ortelius’ contemporary Gerardus Mercator (Gerhard de Cremer). The term is said to be derived from the representation of Atlas supporting the heavens that formed a frontispiece to early atlases. Mercator, who also came from Flanders, was the leading cartographer of the 16th century.

The four generations of the Cassini family of astronomers and surveyors in France were pre-eminent in developing methods for accurately surveying the land surface. In work extending from the late 17th to the late 18th century, the Cassinis made the first detailed topographic survey of a large country, and this was used as the basis for a national atlas of France published in 1791. In the 18th century James Cook set new standards in accuracy and skill in navigation. Furhermore, his voyages had scientific missions. On his famous second voyage (1772-75), which circumnavigated the globe at high southern latitudes, he was accompanied by Johann and Georg Forster, the father and son who made botanical collections and climatological observations. Georg Forster later influenced Alexander von Humboldt to study geography.

During his travels in South and Central America (1799-1804) Humboldt located places with accurate latitudes and reasonably close longitudes. Through his detailed observations in the Andes he was able to provide the first systematic description of the interrelations of altitude, temperature, vegetation, and agriculture in low-latitude mountains and to provide a clear picture of vertical zonation. He plotted his data on maps and coined13 the term isotherm for a line joining points with the same temperatures. In his regional monograph on the economic geography of New Spain (Mexico) Humboldt presented data on population, production, trade, utilization of resources, and their interconnections.

Дата добавления: 2021-10-28; просмотров: 581;