The History of Exploration

Since the earliest times, people have explored their surroundings. They have crossed the hottest deserts, climbed the highest mountains, and sailed the widest seas. They have struggled through steamy jungle to find an unknown plant and brought back weird1 creatures from the ocean floor. All explorers have in common the human trait of curiosity2. However, curiosity was not the only reason for many journeys of discovery. Explorers always had more practical reasons for setting out, for example to search for land or treasure.

Some hoped to find valuable trade or new routes to countries that produced the goods they wanted. There is a saying that “trade follows the flag”. In other words when explorers find new lands, traders will soon follow. However, it would be better to say that “the flag follows trade”! It was the search for trade and trade routes that resulted in3 Europe’s discovery of all the world’s oceans and continents during the 15th and 16th centuries. The famous voyages of explorers, such as Columbus and Magellan, arose from desire of Europeans to find a sea route to the markets of the Far East, where valuable goods like silk and spices could be bought. Columbus did not set out to discover a new continent. He was hoping to reach China and Japan, and died insisting that he had done so. Magellan did not intend to sail around the world. He was hoping to find a new route for trade with the Moluccas4, or Spice Islands.

Some were missionaries, who felt a duty to convert people to their own religion. Unlike many other religions, Christianity claims to be universal5. Sincere Christians therefore believed it was their duty to convert other people to Christianity. European expeditions to the Americas included priests, whose job was not only to hold services for the European members of the expedition, but also to convert the local people.

Some were fishermen or miners or merchants, looking for a better living. One of them was Marco Polo, who made his famous journey to the East in 1271. There were many Europeans travelling across Asia, but Marco’s journey was unique because he stayed in the vast Mongol Empire for 20 years. On his return to Europe he wrote a splendid book describing all that he had seen.

All explorations and discoveries have opened the world. Thanks to the determination of generations of explorers, there is almost no place on Earth that is still unknown and unnamed. We know what lies in the ocean’s depths, and at the top of the highest mountain. Maps chart the dry rocks of the world’s deserts and the glaciers of the coldest polar regions. Even the Earth’s gravity has not stopped explorers from heading out into space6. As distant places have become more familiar, the nature of exploration has changed. The challenge is no longer to discover the world’s wild places. Today, a new adventure in exploration is beginning. Explorers are trying to understand the Earth and its climate, and the living things that inhabit its surface. Scientists hope to learn more about the Earth’s geology and origins by studying and measuring the tiny shifts7 of the bare rocks on mountaintops.

We are finding out about the surroundings of the Earth itself. Now that the Moon has been visited, space scientists today are concentrating on building space stations closer to Earth (highly accurate photographs from the “eyes in the sky” – satellites – help scientists to map the world’s most remote regions, to look for mineral resources, and to track the spread of pollution8 and crop disease9) and sending space probes to find out more about regions of space much farther away. Spacecraft travelling through the solar system have sent back news of other planets and one day men and women will follow them.

For millions of years, the Earth’s natural systems have lived in delicately balanced harmony10. Exploration itself does little to upset this balance. But when people move into newly discovered areas they cause permanent changes. The explorers of the past showed our ancestors the wonders of the Earth. The duty of explorers today is to discover how to preserve these wonders for future generations.

Captain Cook

In the 18th century Europeans knew very little about the South Pacific. Many did not believe it was an ocean at all and thought instead that the region contained a giant southern continent, which stretched across the South Pole and reached as far north as the tropics. The Solomon Islands, New Zealand, and possibly even Australia were all considered part of this huge land mass. Two nations – Great Britain and France – took the lead1 in exploring the South Pacific, but it was an Englishman, Captain James Cook, who solved the mystery of the Southern continent for ever.

The famous navigator was born in Yorkshire in 1728, and he spent his boyhood and learnt his seamanship there. James Cook joined the Royal Navy in 1755 at the age of 27 after serving 10 years in merchant2 ships. Although he joined the Navy at a low level, he was a skilled navigator and pilot and gained rapid promotion3. However, he did not become an officer until 1768, when he was appointed to lead the expedition to the Pacific.

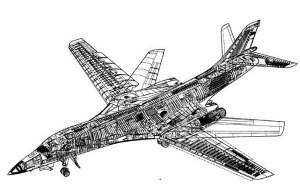

James Cook made three voyages from the British Isles to the South Seas. When he had to choose a ship to sail around the world, he chose a Whitby collier4 and renamed it the Endeavour. Colliers were built to carry coal, so the Endeavour was neither beautiful nor fast, but she was tough5. There was enough room on board for stores and a crew of 94 men, including the wealthy young naturalist, Joseph Banks and his team of scientists.

On his first voyage, in 1768, Cook sailed to Tahiti, New Zealand and the east coast of Australia. To prove this fact his team displayed the British flag on the shore and carved a brief inscription6 on a nearby tree.

Captain Cook first stepped ashore on April 29th, 1770. There was a great variety of plants in the vicinity7 of his landing area, and that’s why he called the place Botany Bay. At Botany Bay, Joseph Banks and the other naturalists collected hundreds of plants they had never seen before. Cook’s crew were the first Europeans to see an Australian Kangaroo. They were totally confused by it and couldn’t decide what kind of animal it might be. It was the colour of a mouse, the size of a deer and it jumped like a hare. In the end they decided it must be “some kind of stag”8. That part of Australia resembled the coastline of Glamorgan and Cook gave it the name of New South Wales. After that he continued his voyage of exploration and discovered that New Guinea was completely separate from Australia. Cook’s charts of the region, showing the Solomon Islands, New Zealand’s North and South Islands, and the east coast of Australia, proved they were separate countries rather than a single continent.

On his second voyage, in 1772, James Cook sailed due9 south into Antarctic waters, and guessed correctly that there was an area of frozen land around the South Pole. Approaching Antarctica he crossed the Antarctic Circle twice. The famous navigator never actually saw Antarctica, the real Southern continent, though he was very close to it several times. “Ice mountains”, as he called the icebergs, prevented him from sailing closer to it. His crew chipped chunks10 of ice from the icebergs to use as drinking water. Cook felt sure the ice stretched all the way to the South Pole, and wrote in his journal that he could think of no reason why any man should want to sail in these cold and dangerous waters again.

On his third voyage, in 1776, Captain Cook sailed to the North Pacific looking for an inlet that would lead him to the Arctic Ocean. On the way, he found Hawaii by chance. Cook came across the Hawaiian Islands, which he named the Sandwich Islands. He spent the winter there getting to know the islands and their inhabitants, who were very friendly. In spring he left to explore the coast of North America but had to return to Hawaii to repair a broken mast. This time the islanders did not welcome the strangers so warmly, perhaps because they were short of food. A quarrel began when some of the islanders stole one of the ship’s boats. A short scuffle11 broke out on the beach and Cook was stabbed12 to death. He died in 1779.

Whitby Museum contains many souvenirs from Cook’s voyages, and there are also scale models of his ships – Endeavour and Resolution, both of which were built right here in Whitby’s shipyards. A splendid life-size figure of the great sailor and explorer stands facing the sea on the West Cliff above the harbour.

The History of Maps

Men have been using maps for thousands of years. In ancient times little was known about the shape of the Earth. Men did not even know that the Earth is round. They never traveled far, so they did not know how large is the Earth. The earliest maps were not accurate, but still they were useful.

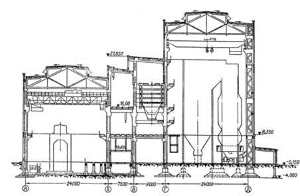

The first known maps were made by the Egyptians as long ago as 1300 B. C., to show the boundary lines of each man’s land. But the first world maps were made by the Greeks. It is supposed that Anaximander had designed the first ones. He was a Greek scientist who lived from 611 to 547 B. C. According to Anaximander’s maps, the Earth was a flat circle surrounded by one large river.

Most European maps in the Middle Ages showed the world as a flat disc. Only three continents were shown – Europe, Asia and Africa, as the existence of the Americas had been unknown. The top of the map was East, and at the exact centre of the world was Jerusalem, the Holy city. Jerusalem was placed at the centre of the Earth because that is where the Bible says it is. Maps such as those were usually published in religious books, and we should really think of them not as maps, but as religious pictures. The Christian Church taught that the Earth is flat. Although the Ancient Greeks knew better, and this knowledge never quite died out, most people believed without question that the earth was flat.

While Christians still believed that the Earth was flat, Muslim scholars knew it is round. The famous Arab geographer Al Idrisi was born in North Africa in about 1100. He traveled through much of Europe and the Near East and worked for many years for Roger II, King of Sicily. He produced a map of the world, a globe of the Earth and a huge guide for travelers. The map even showed a possible source of the Nile, which wasn’t far from the true source.

World maps in the 15th century were based on the work of Claudius Ptolemaeus, known as Ptolemy, an ancient geographer who had been dead for more than 1200 years! Ptolemy map showed Europe and the Mediterranean region quite accurately, but it showed only the top half of Africa because Ptolemy had no idea how far south the continent stretched, nor if it even ended at all. The Portuguese sailors who first rounded the tip1 of Africa kept the reports of their voyages secret from other European nations who also wanted to find a sea route to the trade goods of the Far East.

As years passed and men learned more and more about the geography of the world, maps became better and better. During the 18th and the 19th centuries, France and England sent many explorers to new parts of the world. French and English settlers went to these new places to live. Then, as information got back to France and England, new maps were made.

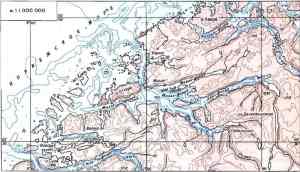

During the 19th century another kind of map was developed. It was called a topographic map. A topographic map is often very detailed. It may cover as little as five square miles, but it shows just about everything there is to show about the geography of that area.

Until the end of the 19th century there were no international agreements about making world maps. The maps made in one country did not agree with the maps made in another country. But in 1913 a meeting of 34 countries was held in Paris. At the meeting a set of rules for making world maps was agreed upon. And today these rules are even more important than ever. They are important because the boundaries of countries are often changed. And changes make new maps necessary.

Дата добавления: 2021-10-28; просмотров: 649;