The origin of day names

| Day names | Germanic god(dess) | His / her status | Roman / Greek gods | Planets and stars |

| Monday | – | – | – | the Moon |

| Tuesday | Tiw | The god of war | Mars / Ares | – |

| Wednesday | Woden | The god of commerce | Mercury / Hermes | – |

| Thursday | Thor / Thur | The God of thunder | Jupiter / Zeus | – |

| Friday | Frigg / Freya | Woden’s wife / the goddess of prosperity | – | – |

| Saturday | – | – | – | the Saturn |

| Sunday | – | – | – | the Sun |

The Anglo-Saxon word-stock consisted mainly of words of the Germanic origin. Most of them have correlations in the Indo-European languages:

Words belonging to the Indo-European Family of languages

| Latin | Modern German | Old English | Modern English | Russain |

| pater | Vater | fWder | father | (патриарх) |

| mater | Mutter | modor | mother | мать |

| frater | Bruder | broTor | brother | брат |

| unus | ein | an | one | один |

| duo | zwei | tu, twa | two | два |

| tres, tria | drei | Þri, Þrie | three | три |

| junior | jung | GeonG | young | юный |

| novus | neu | neowe | new | новый |

| dies | Tag | dWG | day | день |

The invaders were engaged in farming and cattle-breeding. The names of Anglo-Saxon villages usually had the root ham meaning ‘home, house’ or ‘protected place’: Nottingham, Birmingham. The Saxon ton stood for ‘hedge’ or ‘a place surrounded with a hedge’, as in Brighton, Preston, Southampton. The Saxon for ‘fortress, town’ was burG or burh which we now see in Canterbury, Salisbury, Edinburgh; feld meant ‘open country, field’ and it is seen in the names of Sheffield, Chesterfield, Mansfield.

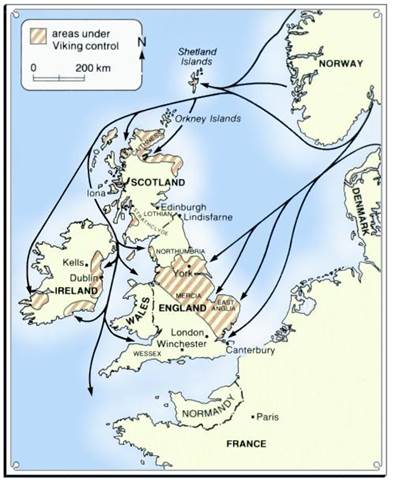

The Danish Invasion of Britain

· Danish raids

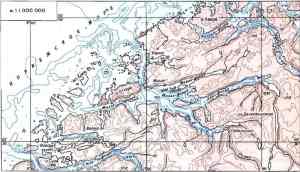

From the end of the 8th and then during the 9th and the 10th centuries Western Europe faced a new wave of barbarian attacks. (See Map 5.) The barbarians came from the North – Norway and Denmark – and were called Northmen. In different countries they were also known as the Vikings, the Normans and the Danes. The word Viking, or pirate was used by their victims and referred equally to the invaders from Norway and Denmark. As Britain was mostly raided from Denmark, in British history the invaders came to be known as theDanes.

Map 5

(From David MacDowell. An Illustrated History of Britain, Longman.)

The expansion of the Scandinavians is a European phenomenon, of which the raids on England and Ireland made only one part. Although they mostly lived in tribes, they were not totally barbarians. They were involved in trade and had regular ties with the nations living to the west and south. Many adventurers must have heard stories about the fertile lands and the rich monasteries overseas which were easy to plunder. The Northmen were well-armed skilful warriors and sailors and could easily cross the sea in search of fortune. But although they were prepared to fight, they usually aimed not at fighting but at getting loot. At the time, Ireland was the chief gold producing country of Western Europe. Moreover, it had not been invaded either by the Romans or the Anglo-Saxons. Now it was one of the first countries to be raided by the Norwegians.

In 793 the Danes carried out their first raids on Britain. In the three successive years they devastated three of England’s most holy places – Lindisfarne, Jarrow and Iona – with the treasures their monasteries possessed. The earliest raids were for plunder only. Cattle was driven off, houses were burnt, monasteries plundered and people slain. Then the invaders would return home for the winter. But a big raid on Kent in 835 opened three decades in which attacks came almost yearly, and which ended with the arrival of an invading army. Thus began the fourth conquest of Britain.

The struggle of England against the Danish attacks lasted over 300 years. During that period of time over half of England was occupied by the invaders and then regained by the English again. The Danish raids were successful because the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms had neither a regular army nor a fleet of ships in the North Sea to resist the invaders. Besides, there were few roads and fortresses as the Anglo-Saxons had destroyed them. Thus, even if a settlement resisted the Danes for some time, it took their messenger several weeks to reach the nearest king and bring help. Soon the Danes conquered Northumbria, East Anglia and Mercia. London was raided in 842 and 851, and in 872 it fell to the invaders. Only Wessex was left to face the enemy. Historically, it was Wessex that became the centre of resistance to the Danes.

· King Alfred the Great

In 878 King Alfred, known in history as Alfred the Great(871-899), managed to win a decisive victory over the Danes and by the peace treaty England was divided into two parts: Wessex, ruled by Alfred, and the north-eastern part of England which was called Danelaw (Danelagh), under the rule of the Danish kings. (See Map 6.)

Map 6

(From S.D. Zaitseva, Early Britain, Moscow, 1975.)

The old Roman road from London to Wales called Watling Street served as the boundary between Danelaw and Wessex; in the North it did not even reach Hadrian’s Wall. The invaders founded new villages and towns in the north of England, which were inhabited by a mixed population of the English and the Danes.

In the Danelaw, the Danes established a society of their own governed by the Danish law. Even when the Danelaw was christianized and brought under English rule, there remained certain peculiarities: land measurement, law and social differentiation.

In 886 King Alfred the Great began to win back Danish-occupied territory by capturing the former Mercian town of London. Four years later he introduced a permanent militia and army. Alfred the Great was

the first English king to establish a regular army: all noblemen and free peasants were trained to fight. The only way of combating raids from the sea was to build ships. Alfred is said to have founded the English navy. He built ships, which were bigger than the Vikings’, carrying 60 oars or more. The places that could be easily attacked by the enemy were fortified. By the late 880s Wessex was covered with a network of roads and burghs, or public strongholds which could be described as planned fortified towns. The neighbouring landowners were responsible for maintainig the fortifications. In return, they were able to use the defences for their own purposes. The 33 fortified towns soon began to play an important part in the local rural economy.

King Alfred devoted the last ten years of his life to reviving literacy and learning in the country. He carried out his programme of education through court intellectuals and priests who were all obliged to know Latin. Alfred’s own contribution to this programme was one of his greatest achievements. He was the only English king before Henry VIII who wrote and translated books. King Alfred drew up a code of Anglo-Saxon laws and translated into English Bede’s Ecclesiastical History as well as the Bible. To him the English owe the famous Anglo-Saxon Chronicle which may be called the first prose in English literature. King Alfred died in Winchester, the capital of Wessex, in 901. He is the only king in English history called ‘the Great’.

· End of the Danish rule

At the end of the 10th century the Danish invasions were resumed. The English tried to buy off the Vikings, and as a result, the Danes imposed on them a heavy tax called the Danegeld in 991. In that year alone, 10,000 pounds of silver were paid.

A new form of local government was introduced at about the same time. The country was divided into shires with one of the king’s local bailiffs (‘reeves’) in each shire appointed ‘shire-reeve’ or sheriff. The sheriff was responsible for collecting royal revenues, in the shire court he announced the king’s will to the local noblemen and took an active part in everyday business. Sheriffs belonged to the growing community of local nobility.

At the beginning of the 11th century the whole of England was conquered by the Danes. The Danish king Cnut, or Canute, became king of England, Denmark and Norway (1016-1035). Canute preserved many of the old Saxon laws collected by Alfred. He became a Christian and a protector of monasteries. Although Canute made England his residence, he often had to leave England for Denmark. Canute had to make English government function during his absence that is why he divided the kingdom into 4 earldoms: Wessex, Mercia, Northumbria and East Anglia. The king appointed an earl to rule an earldom. Gradually, the earls became very powerful. They were both Danes and Anglo-Saxon noblemen. Supported by the Anglo-Saxon feudal lords, Canute reigned in England until he died.

· Culture and language of the period

The influence of the Danes on the development of English culture and the language should not be underestimated. During the Danish invasion of England, the language underwent considerable changes. The Danes were of the same Germanic origin as the Anglo-Saxons themselves and came from the same part of the Continent. As the roots were the same in English and Danish and the languages assimilated, case endings were dropped and new grammar forms developed to show relations of words. The dropping of endings meant that the stress was changed, the sound and rhythm of the language became different. Many English words are of the Scandinavian origin:

| English | Scandinavian |

| fellow | feolaGa |

| husband | husbonda |

| law | laGu |

| wrong | wrang |

| to call | kalla |

| to take | taka |

The Scandinavian borrowings in English are such adjectives as happy, low, loose, ill, ugly, weak; the nouns sister, sky, window, leg, wing, harbour. The names of Danish settlements often ended in –by or –toft/thorp(e) which meant ‘village, settlement’. Thus we have Derby, Grimsby, Whitby, Lowestoft, etc.

Old English was a synthetic language. It expressed relations between words and expressed other grammatical meanings with the help of suffixes, prefixes and interchanges in the root. The noun had the categories of number, gender (masculine, feminine, neutral), declension (ending in different letters), and case (Nominative, Genitive, Dative, Accusative). Strong and weak verbs were conjugated in the Present and the Past. A future action was expressed by means of a Present tense. During the Danish invasion prepositions and pronouns were used more often than before.

Edward the Confessor

The Danish dynasty ruled England up to 1042 when the English throne went to Edward the Confessorthe eldest son of the Saxon king Aethelred and Emma of Normandy. He restored the Saxon rule but boosted Norman influence in England.

During the Danish rule Edward lived in Norman exile. When he returned to England as king, he brought a large number of Norman monks and noblemen to whom he began to give the richest lands and high government positions. Edward did not only speak French himself but insisted on it being spoken at his court. During his reign there was a constant struggle between the Norman influence at court and the power of Saxon earls. Edward was unable to control the nobility, especially Earl Godwin, whose daughter was his wife. Edward himself was more interested in the Church than in state affairs and led a monastic life building churches. By the time he died, there was a church practically in every English village. King Edward also founded Westminster Abbey.

Upon the death of Edward the Confessor, the Saxon Witan was to decide who would get the English throne. One of the claimants was Harold, the son of Earl Godwin. The other was William, the Duke of Normandy.

| DO YOU KNOW THAT · Bath, the famous resort, was founded by the Romans. · The first English non-runic texts written in Latin letters were glosses, or translations of Latin religious texts written between the lines in Gospels. · The Danes introduced in England the use of chairs, benches and beds. · The game of chess was brought to England by the Danes. · The first English uniform currency based on silver pennies was introduced in 973. | ? |

Beginning of the Norman invasion

· Origin of the Normans

In the 9th century, while the Danes were plundering England, another branch of Northmen, also related to the Danes, were raiding the northern coast of France. They came to be called Normans, a variation of the word ‘Northmen’. The Danes settled down in the conquered part of England called the Danelaw. Likewise, the Normans settled down on the land conquered from the French king – a territory which is still called Normandy.

As time went by, the Danes mixed with the Anglo-Saxons, who were themselves of Germanic origin, and retained their Germanic language, customs and traditions. As for the Normans, they were now quite different from their Teutonic forefathers. They lived among the French who were a different people and spoke a different language – belonging to the Romance group. The Normans assimilated with the French population of the conquered territories, adopted their culture and a certain dialect of the French language. The establishment of the feudal system in France had been completed by the 11th century, and the Norman barons had come into possession of large tracts of land and a great number of serfs.

The Normans lived under the rule of the Duke of Normandy. In the 11th century, the Dukes of Normandy officially acknowledged the King of France as their overlord, but, like other dukes and counts of France, they had made themselves practically independent. They were as strong as the king himself, whose domain was smaller than the Duchy of Normandy. They coined their own money, made their own laws, held their own courts and built their own castles. As a well-trained cavalry, the Norman knights were the best in Europe. They were formidable fighters and would wage wars so as to seize new lands and serfs.

· Claimants to the English throne

The question who should follow Edward the Confessor as king was one of the most important in English history.

In the last ten years of his rule, King Edward heavily relied on his brother-in-law, Harold Godwin. Being childless, the English monarch is believed to have named Harold as his successor. At the same time, it was known that Edward had promised the English crown to his grand-nephew William, the Duke of Normandy, in return for his support. Edward’s death started the struggle for the English throne. The third claimant for the English throne was King Harold Hardrada of Norway.

When the Witan, or council of wise men, chose Harold Godwin as King of England, William of Normandy began preparations for the war. He sent messengers far and wide to invite the knights of Europe to his army. William called upon all Christians in Europe to help him gain the rights to the English throne. He also gained the support of the Pope promising to strengthen the influence of Rome in England. Although no pay was offered, the army was raised quickly because William promised land.

Harold Godwin reigned for less than a year. In the summer of 1066 the Norwegians headed by Harold Hardrada invaded Northumbria and occupied York. Harold Godwin marched northwards and met Hardrada at Stamford Bridge where the Norwegians were defeated in a fierce battle on September 25. Three days later Duke William’s fleet, which had been delayed by bad weather, landed at Pevencey. On hearing the news, King Harold had to rush south 250 miles in nine days.

· Battle of Hastings

The English and Norman armies met on October 14, 1066, in the neighbourhood of Hastings. The Normans outnumbered the Anglo-Saxon forces and were superior in quality. The Normans used a skilful combination of heavy-armoured cavalry and archers. First, the archers would break up the ranks of the enemy, then followed a charging cavalry which decided the victory.

Map 7

The Anglo-Saxons had a small cavalry which was mainly Harold’s bodyguard. The English footmen usually fought in a mass standing close together, so as to form a wall of shields to protect themselves. The hastily gathered peasants were armed with pitchforks, axes or thick oak poles and could not hold out long against the well-armed and armoured Normans. Even the skilled Saxon archers did not pose danger to the Normans who wore armour, as there was little chance that many of them could be killed by Saxon arrows.

The battle lasted the whole day. Despite their tiredness after a long march, the English had the initial advantage, since they were fighting for their independence. But in the end the Normans’ discipline prevailed. Harold died fighting, cut down by a sword (not, as often said, struck by an arrow). Gradually the Saxon rows thinned and finally the Normans succeeded in breaking the line of defence. The battle was over. William ordered Harold to be buried with all the royal honours and then marched to London.

Harold’s death ended England’s 600 years of rule by Anglo-Saxon kings. The Witan proclaimed William king of England and on Christmas Day 1066 the Duke of Normandy was crowned as William I in the new church of Westminster Abbey. In history he is more often referred to as William the Conqueror. He ruled England for 21 years, from 1066 to 1087.

The Norman Conquest

· Lands and vassals

As a result of the Norman invasion, England did not only receive a new royal family but also a new ruling class, a new culture and a new language. The victory at Hastings was only the beginning of the Conquest. Despite the surrender of London and Winchester it took William and his barons over 5 years to subdue the whole of England. There were risings against Norman rule in every year from 1067 to 1070. William ruthlessly put down local revolts. His knights raided villages and towns, burning and slaying everything and everybody. After several risings in the North, the lands of Northumbria were raised to the ground. Every house or cottage between Durham and York was burnt down, people were massacred, crops were destroyed and cattle were driven off. It took Northumbria almost a century to recover.

William organised his English kingdom in accordance with the feudal system which was based on ownership of land. The Conqueror declared that all the lands of England belonged to him by right of conquest. One-seventh of the country was made the royal domain which consisted of 1420 estates. The monasteries were granted 1700 estates. The Anglo-Saxon landowners and clergy were turned out of their houses, estates and churches. More than 4,000 Saxon lords were replaced by a group of less than 200 Norman barons. By 1086 there were only two surviving English lords of any importance.

While all land was owned by the king, part of it was held by the king’s vassals, in return for services and goods. Those were the knights who had taken part in the Conquest, and the Anglo-Saxon lords who supported the Conqueror. The greater nobles gave part of their lands to lesser nobles and other “freemen”. Some freemen paid for the land by doing military service, while others paid rent. The noble kept “serfs” to work on his own land. They were not free to leave the estate, and were often little better than slaves.

The two basic feudal principles implied that every man had a lord, and every lord had land. On getting his estate, each Norman nobleman became the king’s vassal as he swore an oath of allegiance which said: “I become your man from this day forward, and to you shall I be true and faithful, and shall hold faith for the land I hold from you.” William made both the great barons and their vassals swear allegiance to him directly. In 1086, at a gathering of knights in Salisbury, William made them all take a special oath to be true to him against his enemies. Thus, the European rule “my vassal’s vassal is not my vassal’ was broken in England. In other words, if a baron rebelled against the king, his immediate vassals were obliged to fight for the king.

· The Domesday Book

By 1086 the Conqueror wanted to know exactly who owned which piece of land, and how much it was worth. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says: “In 1086 William the Conqueror sent his men all over England, into every shire to find out what property every inhabitant of England possessed in land, or in cattle, and how much money this was worth.” He needed this information to know how much was produced and how much he could ask in tax. That was the first registration and complete economic survey in England. Each  manor was described according to value and resources. Every man who owned or rented land was questioned and threatened to be punished on doomsday if he did not answer the questions of the king’s men as to how much land there was; who owned it; how much it was worth; how many families, ploughs and sheep there were, etc. As a result of the registration, the majority of the population were registered as unfree peasants, or serfs. They made 79 per cent of the total population of England.

manor was described according to value and resources. Every man who owned or rented land was questioned and threatened to be punished on doomsday if he did not answer the questions of the king’s men as to how much land there was; who owned it; how much it was worth; how many families, ploughs and sheep there were, etc. As a result of the registration, the majority of the population were registered as unfree peasants, or serfs. They made 79 per cent of the total population of England.

Domesday was one of the greatest administrative achievements of the Middle Ages. It assisted the royal exploitation of crown lands and feudal rights, and provided the new nobility with a formal record and confirmation of their lands thus putting a final seal on the Norman occupation.

The original copy of the Domesday Book, in several volumes, still exists, and provides an extraordinary amount of information about England at that period of time.

The original copy of the Domesday Book, in several volumes, still exists, and provides an extraordinary amount of information about England at that period of time.

· Castles

To further strengthen his power, William built 78 castles throughout the country. Ironically, the Normans used the labour of the conquered Anglo-Saxons to erect the fortresses which would be used to suppress the native population. The main purpose of the castle was to house the Norman cavalry which would find shelter inside in time of danger and from which they could start on their raids.

A Norman castle was often built on a hill or rock. First, the peasants would dig out a moat and make a drawbridge, and then use the removed soil to make the hill higher. Then they would build a wooden tower on top of the hill and surround it with a wooden wall, wide enough for archers to walk along. The outer wall was strengthened with towers built on each corner. Later the wooden structures were replaced by stone keeps. The castle usually dominated the nearest town, village or countryside.

Most of the castles were royal property. A baron could build a castle only if he was granted the king’s special permission. The first Norman stone castles were the Tower of London, the castle of Durham and Newcastle on the river Tyne. Some castles, such as Windsor Castle, are still used as residences.

England in the Middle Ages

· Royal power

William I began the rule of a dynasty of Norman kings (1066-1154) and entailed the replacement of the Anglo-Saxon nobility with Normans, Bretons and Flemings, many of whom retained lands in northern France. Instead of the Saxon Witan, William established the Curia Regis (1066) which existed until the end of the 13th century. It had the functions of government and king’s court in the early medieval times. Although William let the English keep their own courts and laws, the judges were Norman.

Another change introduced by William was the abolition of the earldoms of Northumbria, Mercia and Wessex, which had been established by King Canute. Now the country was divided into counties which were ruled by sheriffs appointed by the king.

Between 1066 and 1144 England and Normandy were united under one king-duke. The result was the formation of a single cross-Channel political community. Since Normandy was a principality ruled by a duke who recognised the king of France as his overlord, this also meant that from now on English politics became part of French politics. The two countries shared not only a ruling dynasty, but also a single Anglo-Norman aristocracy. It lasted until 1204.

After his death in 1087, William I was succeeded by his sons and nephew (William II, Henry I, Stephen) and finally by his granddaughter’s husband Henry II of the House of Anjou also known as the Plantagenet. Royal power was strengthened and the Anglo-Norman kings acquired new territories both on the British Isles and on the Continent.

As duke of Normandy, duke of Aquitaine (by his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine), and count of Anjou Henry II had inherited lordship over the respective and neighbouring territories. In England, he managed to strengthen royal power and win back the northern English territories which had been occupied by Scotland. Henry II was king of an empire stretching from the Scottish border to the Pyrenees, probably the most powerful ruler in Europe, who was richer than the emperor of the king of France. (He was the lord of Paris, Blois, Normandy, Flanders, Brittany, Burgundy, Champagne, Anjou, Aquitaine, Gascony and Toulouse on the Continent and of England and part of Ireland across the Channel.) The source of his wealth was in England, his wife’s homeland, but the heart of the empire lay in Anjou, the land of his fathers. Out the thirty-five years of his reign, Henry II spent twenty-one on the Continent. In England, he confiscated or ruined the castles built without royal authority and curbed the power of the nobles. He introduced trial by jury and established Anglo-Saxon common law as the law of England.

· Church and State

During the reign of Henry II (1154-1189) there happened an event which had a powerful effect on the history of English Church and social life in the country.

In order to strengthen monarchy, Henry II made his friend Thomas Becket first Chancellor and then Archbishop of Canterbury. Becket, a merchant’s son, was known to be a sinner and an ardent supporter of the king. But when Becket became Archbishop of Canterbury he got completely reformed. Within a few years he became one of the most respected priests in England. The greatest problem was that now he was trying to prove to Henry that royal power was inferior to God’s power and Papal power, and that was quite the opposite to what Henry had expected him to do. The former friends turned into bitter enemies, and finally Becket had to flee to France. He visited Rome where he got the Pope’s blessing and several years later returned to England to continue strengthening the position of the Church. He landed in an unexpected place and avoided Henry’s men, who had been sent to kill him. Shortly afterwards, in 1171, Thomas Becket was killed in Canterbury Cathedral by the four barons sent by the king. The murder in the Cathedral shook the country. Henry had to admit that it was a political murder, an assassination. But Henry II had achieved his aim and royal power was strengthened. In two years’ time Becket’s tomb became a centre of pilgrimage, and in 1173 Thomas Becket was canonised.

One of the masterpieces of English literature, “The Canterbury Tales” written by Geoffrey Chaucer in the 14th century, is based on the stories told by a group of pilgrims travelling to the tomb of Thomas Becket in Canterbury Cathedral. Two outstanding figures in world literature of the 20th century, Jean Anouilh of France and T.S. Eliot of Britain, a Nobel Prize winner, wrote respectively “Thomas Becket” and “Murder in the Cathedral”. The central idea of each piece is the antagonism between friendship and duty, friendship and treachery for the sake of the state.

Henry II’s son Richard known as Richard the Lion Heart was one of England’s most popular kings, although he spent only six months of his reign in England. He was brave, cruel and generous, and inspired loyalty. With other Christian leaders Richard I headed the Third Crusade against Muslim rule in the Holy Land and secured Christian access to the holy places. Richard was a superb military leader and a fine troubadour-style lyric poet, but his wars on the Continent cost England a lot of money and weakened the crown which, during his absence, was usurped by his wicked brother John.

· Magna Carta and the beginning of Parliament

After Richard’s death, when John became lawful king of England, he lost Normandy and other territories in the wars against the king of France. His vassals came over to England to receive lands and titles. John began to give the lands and castles of the first Norman barons, who had come with the Conqueror, to the newcomers. Hatred for King John united the old barons, bishops and the Anglo-Saxons in their almost open struggle against the king. In the civil war which broke out, the barons worked out a programme which King John was finally forced to sign and seal. Magna Carta, or the Great Charter, was signed on June 10, 1215. The document was a detailed statement of how the king’s government ought to work and what kind of relations there ought to be in a feudal state between the monarch and his vassals. Instead of paying their lords in services, some vassals paid them in money. Vassals were beginning to turn into tenants. Feudalism, the use of land in return for service, was weakening. But it took three hundred years more to get rid of feudalism.

Magna Carta was the first document to lay the basis for the British Constitution.

When the throne went to Henry III, he tried to centre all power in his hands. Several times he demanded money from the Great Council but the barons refused to grant money. The first attempt to curb the power of the king and his foreign advisers was made by Simon de Montfort, the leader of the lesser barons and the new merchant class and poorer clergy. In 1258 they took over the government and elected a council of nobles which de Montfort called parliament(from the French word “parler” - “to speak”). The nobles were supported by the towns, which wished to be free of Henry’s heavy taxes. In 1264 a civil war began and the incompetent king was defeated. In 1265 de Montfort became the virtual ruler of the country and called “two knights from every shire, two burgesses from every borough” to his parliament The first Parliament was quite a revolutionary body. It represented the interests of barons, the clergy and the new class of merchants.

During the reign of Henry III’s son, Edward I, it was granted by the king that no new taxes would be raised without the consent of Parliament. At the end of the 13th and the beginning of the 14th centuries, Parliament was divided into the Lords (the barons) and the Commons (the knights and the burgesses). The alliance between the merchants and the squires paved the way to the growth of parliamentary power. Edward I conquered Wales and made it a principality of England (1284), passed exclusively to the heir to the English throne (Prince of Wales; 1301).

Language of the Norman Period

The Norman period in the English language, which lasted from the 11th to the 15th century, is known as Middle English. The Conquest was not only a historical event, it was also the greatest single event in the history of the English language.

One of the most significant consequences of the Norman domination was the use of the French language in many spheres of English political, social and cultural life. But though the court and the barons spoke Norman-French and the clergy spoke and wrote Latin, the invasion of these two Romance languages could not subdue the popular tongue spoken by peasants and townsfolk all over England. The two main languages, French and English, intertwined and by the end of the 14th century made one language, which was used both in speech and in writing. English was bound to survive and win in this linguistic battle as it was the living language of the people in their native land, and part of their culture. At the same time, Norman-French was torn away from its roots and had to surrender, although it greatly influenced English.

Three hundred years after the Norman Conquest, in 1258, Henry III issued a “Proclamation” to the counsellors elected to sit in Parliament from all parts of England. It was written in threeofficial languages: French, Latin and English. This was the first official document to be written in English. In 1349 it was ruled that schooling should be conducted in English and Latin. In 1362 Edward III gave his consent to an act of Parliament proclaiming that English should be used in the law courts because French had become “much unknown in the realm”. In the same year Parliament, for the first time, was opened with a speech in English.

But the three hundred years of French domination in many spheres of life affected the English language more than any other single foreign influence before or after. The impact of French upon the vocabulary can hardly be exaggerated: the numerous borrowings reflect the spheres of Norman influence on English life.

The phonetic structure of the language was, naturally, affected. It is, however, controversial whether it was only the French language that affected the grammatical structure of English. The need to bring together the language of the new lords of the land and the language of those who cultivated the land brought about considerable changes in the grammar of the Old English language. Endings began to give way to auxiliary verbs. Thus Middle English is known as the period of levelled endings, a transitional period from synthetic forms (with various endings) to analytical forms (the use of auxiliary verbs).

In its turn, the French language brought in a number of new suffixes and prefixes:

· -ance, -ence: ignorance, experience

· -ment: government, agreement

· -age: village, marriage

· -able: available, admirable

· dis-: disbelieve, disappear, distaste.

The suffixes gave an abstract meaning to the words and were also used to form new words from the English roots: unbearable, readable, etc.

It was during the Middle English period that the indefinite article a/an, stemming from the Old English numeral an (one), came into use. Spelling changed altogether. Instead of the Germanic runes Þ and T the Normans introduced the digraph th. The Old English uwas changed into ou or ow as in hus>house, mus>mouse, cu>cow. It should be noted that at the time ou/ow was pronounced as [u:] and the diphthongs [ou]/[au] appeared later.

The Norman period enriched the English language with synonyms. Linguistic practice shows that words denoting the same object or the same idea cannot coexist in the same language, that is why there practically can be no full synonyms in a language. With the inflow of French words into the language, English retained the Anglo-Saxon words denoting things or concepts that the language had had before, and borrowed the French words which gave a new idea or a new shade of meaning. Thus the words ‘to eat, land, house’ come from Old English, but ‘to devour, territory, building’ come from French. The words describing feudal relations or related to the law courts and governing were borrowed from French: to command, to obey, baron, council, to accuse, court, crime, arms, guard, battle, victory, etc.

Even if both Anglo-Saxon and French words remained in the language, they were at least slightly different in meaning. This was illustrated by Walter Scott in Ivanhoe: a domestic animal in the charge of a Saxon serf was called by its Anglo-Saxon name, but when it was sent to the table of a Norman baron it changed it name into French. Thus the English language still has such pairs of words as ‘ox – beef’, ‘calf – veal’, ‘sheep – mutton’, ‘swine – pork’.

Some synonymous words are used in different styles. The English words usually give a homelier idea, while the French ones are mostly used in formal speech: ‘to give up – to abandon’, ‘to give in – to surrender’, ‘to come in – to enter’, ‘to begin – to commence’, ‘to go on – to continue’.

As a result, the stock of synonyms in English is larger than in any other European language, and the English word-stock is the largest in Europe.

The development of culture

The 11th-12th centuries was a period of significant changes in English culture due to the Norman Conquest and the influence of Norman culture on the English court and the nobility. It was a transitional period from Old English and Anglo-Saxon literature of the conquered on the one hand, and the Norman French and continental French literature and the conquerors, on the other hand, to a new language and a new people, with their specific culture.

The 13th century in Britain witnessed an intellectual development which established Britain’s reputation as equal to the continental centres of learning. Central to this was the founding of the two great universities at Cambridge and Oxford.

· First universities

Originally, the first universities in Europe appeared in Italy and France. A fully developed university comprised four faculties: three superior faculties – Theology, Canon law, Medicine – and one inferior (primary) faculty of Art where music, grammar, geometry and logic were taught. University graduates were awarded with 3 degrees: Bachelor of Science, Master of Arts and Doctor. Towards the end of the 13th century there appeared colleges where other subjects were taught. It became a custom with students to go about from one great university to another, learning what they could from the most famous professors of the time.

Already at the end of the 11th century Oxford was a centre of learning. In the middle of the 12th century, after controversial debates at Paris University, a group of professors were expelled. They went over to England and in 1168 founded schools in Oxford which formed the first university. Students and scholars were attracted to to Oxford where they tried to recreate the style of learning they had experienced in Europe. However, the plague, which devastated whole towns, led to a temporary dispersion of the schools. In 1214 the university received a charter from the Pope, and by the end of the 13th century four colleges had been founded: University, Balliol, Merton and St. Edmund Hall. There were already 1500 students and the university was famous all over Europe.

Another university was founded in Cambridge. It is generally considered to date from 1209, when a group of students who had been driven out of Oxford by serious rioting came to Cambridge to continue their studies. Following a Papal Bull of 1318, Cambridge was declared a ‘studium generale’ or place of general education, which meant that degree holders could teach in any Christian country.

Unless a university student was a member of a religious house, it was necessary for him to provide for his own board and lodgings, and usually he would reside with a family in town. This caused certain problems: the young students, who were usually 14 or 15 years old, were often ill-disciplined and needed supervision and financial aid as the landlords often charged them more than other tenants. That led to the opening of colleges, with their hostels and the first student grants which were paid by benefactors and charity funds.

The nobles generally had no use for university education in the Middle Ages. It was the sons of the lower middle-class families who hoped to better their stations in life by getting an education. Most of the English writers and poets of the time had university education.

· Literature of the 11th-13th centuries

The Norman barons were followed to England by the churchmen, scribes, minstrels, merchants and artisans. Each rank of society had its own literature. Monkswrote historical chronicles in Latin. Scholars in universities wrote about their experiments - also in Latin. Even religious satires were written in Latin. The aristocracy wrote their poetry in Norman-French. But the peasants and townspeople made up their songs and ballads in Anglo-Saxon.

The literature of the 11-12th centuries was represented by the romance, the ballad, the fable and the fabliau. The fable and the fabliau were typical literary forms of the townsfolk. Animal characters in fables mocked out human evils and conveyed a moral. Fabliaux were short funny stories about cunning crooks and unfaithful wives written as metrical tales.

The influence of continental literature was marked by the increasing popularity of French chivalric romances – a form already popular in France and Germany, which revolved around the love of a knight for a lady, with definite religious undertones. In southern France the lyric poets of the Middle Ages called ‘troubadours’ wrote dancing-songs called ‘ballads’ (stemming from the same root as ‘ballet’).

The most famous poet in the reign of Henry II was the Norman poet Wace. An educated person who had studied theology at Paris University, he was a clergyman, a secretary, a teacher, a writer and a poet. His chief works were two rhyming chronicles written in form of romance: Brut, or the Acts of the Britts and Rollo, or the Acts of the Normans.

Of great importance was the introduction into English of the Arthurian legend, first in 1140 by Geoffrey of Monmouth in his Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Britons) and then by Wace who translated History of the Britons into French. Geoffrey of Monmouth had been brought up in Wales and lived close to the myth of King Arthur, the legendary Celtic chief.

Later, in the 13th -15th centuries there appeared a series of legends about King Arthur and the knights of the Round Table. The best-known legends are “Arthur and Merlin”, “Lancelot of the Lake”, “Percival of Wales”, “Sir Tristram” and others. In the 15th century Thomas Malory collected Arthurian stories and arranged them in twenty books.

Soon another powerful myth gained popularity, that of Robin Hood and his merry men, the outlaws who would not accept Norman rule but lived free in Sherwood Forest.

Norman kings, who were fond of hunting, turned vast territories into King’s Forest. (The word ‘forest’ comes from the Latin word ‘fores’ which means ‘out of doors’.) It was not a wood, though some parts of King’s Forest were wooded. King’s Forest was carefully guarded: peasants could neither make their living by hunting nor cut trees or shrubs nor pick firewood. Sheep and cattle that had the right to feed in the forest were branded with a special mark and their owners paid taxes. Unbranded animals, if caught, were made royal property. No goats were allowed in the forest as deer hated their smell and would not feed in the place where goats had walked. A man who killed a deer in the forest was either blinded, or had his fingers or arm cut off, or even put to death.

No wonder rebellious peasants, serfs and people who were driven to despair by hunger and need hunted in the forest, thus becoming outlaws.

Ballads describe Robin Hood, the famous legendary outlaw of the period as a strong, brave and skilful archer. Robin Hood was presumably a Saxon nobleman who had been ruined by the Normans. Together with his merry men (Little John – a gigantic manly fellow, brother Tuck – a stray friar and the others) they fought against Norman nobles and clergy and would appear wherever the poor were in need of help. Ballads about Robin Hood were composed and sung throughout the 12th and the 13th centuries. Robin is supposed to have lived in the reign of King Henry II and his son Richard the Lion Heart. All through the ballads goes the idea of Robin waiting for Richard the Lion Heart to return. Then he would lay his bow at the king’s feet and subdue to the lawful king, whose wicked brother John had taken his place while Richard went crusading.

· Art and architecture in Norman England

Art and architecture in the 12th century were especially influenced by continental developments. In addition, crusaders returning from the Holy Lands brought back Byzantine influences. One of the four most unusual churches, the Round Church in Cambridge, is the oldest of the four surviving Norman churches built in 1130. The style was introduced by the returning crusaders in remembrance of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.

The production of illuminated manuscripts increased as new religious orders and monasteries were founded. The use of elaborate initials of these manuscripts was accompanied by a variety of depictions of events, monsters and people which became increasingly sophisticated as the century progressed, until this Romanesque illumination became Gothic. In architecture, the 12th and 13th centuries also experienced this transition, with the development of the early Gothic style. It was in this style that the original Westminster Abbey was constructed from 1245.

| DO YOU KNOW THAT · King Harold Godwin’s elder daughter Gytha married Prince Waldemar of Novgorod, later King Waldemar of Kiev, and became Queen. · William the Conqueror, the illegitimate son of the Norman duke Robert the Devil, was also known as William the Bastard. · The Bayeux Tapestry (1067-1077), an embroided wall-hanging in coloured wool on linen, narrating the events leading up to the invasion of England by William the Conqueror and the Battle of Hastings in 1066, is believed to have been made by William’s wife Matilda and her ladies in waiting. · In 1940, when Britain was desperately fighting against fascist Germany, there circulated a rumour that King Arthur, who would never die, had come again to drive out the expected invader. | ? |

General characteristic of the period

In England the period of the 14th and 15th centuries is known as the period of war, plague and disorder. The country waged long and costly wars with France and the Low Countries on the Continent as well as with Scotland and Wales within the British Isles. The period also saw the longest civil war in English history, the Wars of the Roses. Like nowhere else in Western Europe, the English regularly murdered their kings and the children of their kings. Famine, disease and plague dramatically reduced the population of the country by the beginning of the 15th century. Spiritual uncertainty led to the spread of heresy which swept the country. The oppression of peasants led to numerous revolts.

At the same time, the Continental wars gave Englishmen a sharper sense of national identity and the civil wars finally resulted in the establishment of an absolute monarchy. The peasants’ revolts led to the abolition of serfdom. Some heretical priests turned into famous poets.

The growing economic development of England turned it into one of the strongest European powers.

·  Population

Population

English society was headed by the king and based upon ownership of land. The richest landowner was the king who was followed by the landed nobility: dukes, earls and knights who were no longer heavily armed horsemen but had turned into ‘gentlemen farmers’ or ‘landed gentry’.

| King i | ||||||

| Landowners | ||||||

| Lords dukes earls knights | Clergy monasteries bishops | |||||

| Freemen | ||||||

| Town | Countryside | |||||

| merchants lawyers artisans workers | peasants farmworkers | |||||

| Serfs | ||||||

By the order of king Edward I all those with an income of 20 a year were made knights, even some of the yeomen farmers and formers esquires became part of the ‘landed gentry’. The word esquire was commonly used in written addresses. Vast lands belonged to the clergy – monasteries and bishops.

Freemen from towns could make a fortune through trade. A serf could become a freeman if he worked for seven years in a town craft guild. Merchants, lawyers and artisans were forming a new middle class. It was knights from the country and merchants from towns that formed the House of Commons in Parliament. The alliance between the landed gentry and merchants made Parliament more powerful.

Judicial power was exercised by the king’s courts as well as justices of the peace who were first appointed by King Edward III to deal with smaller crimes and offences. The JPs were usually less important lords of representatives of the landed gentry. Through the system of JPs, the landed gentry took the place of the nobility as the local authority. The JPs remained the only form of local government in rural areas until 1888. They still exist within the British judicial system.

By the end of the 13th century, England’s population reached its peak of about four million. As there was not enough cultivated land to ensure all peasant families with an adequate livelihood, low living standards and poor harvests led to poverty, disease and famine.

· The Black Death

Longer lasting and more profound were the consequences of a terrible disease called the ‘pestilence’. It was bubonic plague commonly known as the Black Death. The first attack occurred in southern England in 1348 and by the end of 1349 it had spread north to central Scotland. Two more outbreaks of plague fell on 1361 and 1369.

The disease was brought over to England from France in rat-infected ships. There was no escape from it: those affected died within 24 hours. By 1350, the Black Death reduced England’s population by about a third. About 1,000 villages were destroyed or depopulated.

With the reduction of labour available to cultivate the land, land owners were forced to offer wages instead of the old feudal traditions to keep their tenants. The remaining craftsmen and traders charged higher rates. All that brought the possibility of social change in the former strictly stratified society.

In 1351 Parliament passed a law called ‘The Labourers’ Statute’ which obliged any man or woman from 16 to 60 to work on the land if they had no income of their own. Those who disobeyed were executed. The law was the first attempt to control wages and prices by freezing wages and the prices of manufactured goods and by restricting the movement of labour. The peasants who survived the Black Death were forced by drastic measures to till the land of their lords for the same pay that had existed before the epidemic.

In 1377, 1378 and 1360 Parliament voted for the Poll Tax: it was a fixed four-penny tax paid for every member of the population (‘poll’ meant ‘head’). Both ‘The Labourers’ Statute’ and the Poll Tax were significant factors leading to the 1381 Peasants’ Revolt.

· Peasants’ Revolt

In 1381 the impoverished peasants and townsmen revolted. Sixty thousand people led by Wat Tyler and Jack Straw marched from Essex and Kent to London. They besieged the Tower of London where King Richard II and his court had found refuge. Central power was paralyzed. The rebels destroyed the Royal Courts, several prisons, killed the king’s men, beheaded the archbishop of Canterbury and nailed his head to the gates of the Tower. On June 14 the rebels met the king at Mile End, in the suburbs of London. Wat Tyler handed Richard their demands which later became known as the ‘Mile End Programme’. Richard, who was only 14 years of age at the time, met all their demands. He abolished the ‘Labourers’ Statute’ and serfdom. Part of the rebels left the place, bearing the king’s charters which granted them freedom. But the more radical part remained and continued the talks on the following day, in Smithfield. It was there, in Smithfield, that the leader of the revolt, Wat Tyler, was treacherously killed. The rebels were dispersed and punished. Over 100 of them were hanged. But as a result, serfdom was practically done away with by the end of the 14th century. It paved the way to a new social system.

Economic development of England

Already between the 12th and the 14th centuries, new economic relations began to take shape within the feudal system. The peasants were superseded by the copy-holders, and ultimately, by the rent-paying tenants. The crafts became separated from agriculture, and new social groups came into being: the poor townsmen (artisans and apprentices), the town middle class and the rich merchants, owners of workshops and money-lenders. The peasants who wished to get free from their masters migrated to towns. The village craftsmen travelled about the country looking for a greater market for their produce. They settled in the old towns and founded new ones near big monasteries, on the rivers and at cross-roads.

· Agriculture and industry

In the late Middle Ages, England’s wealth was its land. Farming and cattle breeding were the main rural occupations. Corn and dairy goods were the main articles of agricultural produce.

England’s most important industry, textiles, was also based on the land, producing the finest wool in Europe. By 1300 the total number of sheep in England is thought to have been between 15 to 18 million.

As the demand for wool and cloth rose, Britain began to export woollen cloth produced by the first big enterprises – the manufactures. Landowners evicted peasants and enclosed their lands with ditches and fences, turning them into vast pastures. Later, Thomas More wrote about the sheep on pastures: ‘They become so great devourers and so wylde that they eat up and swallow down the very men themselves’. (The phrase is often quoted in Russian as “овцы съели людей”.) In English history this policy is known as the policy of enclosures.

Other industries were less significant in creating wealth and employing labour, although tin-mining in Cornwall was internationally famous.

The new nobility, who traded in wool, merged with the rich burgesses to form a new class, the bourgeoisie, while the evicted landless farmers, poor artisans and monastic servants turned into farm laborers and wage workers or remained unemployed and joined the ranks of paupers, vagrants and highway robbers.

· Wool trade

Trade extended beyond the local boundaries. The burgesses (the future bourgeoisie) became rich through trading with Flanders, the present-day Belgium. The English shipped wool to Flanders where it was sold as raw material. Flanders had the busiest towns and ports in Europe and Flemish weavers produced the finest cloth. Flemish weavers were often invited to England to teach the English their trade. However, it was raw wool rather than finished cloth that remained the main article of export. All through the period Flanders remained England’s commercial rival.

As the European demand for wool stood high, and since no other country could match the high quality of English wool, English merchants could charge a price twice as high as in the home market. In his turn, the king taxed the export of wool as a means of increasing his own income. Wool trade was England’s most profitable business. A wool sack has remained in the House of Lords ever since that time as a symbol of England’s source of wealth.

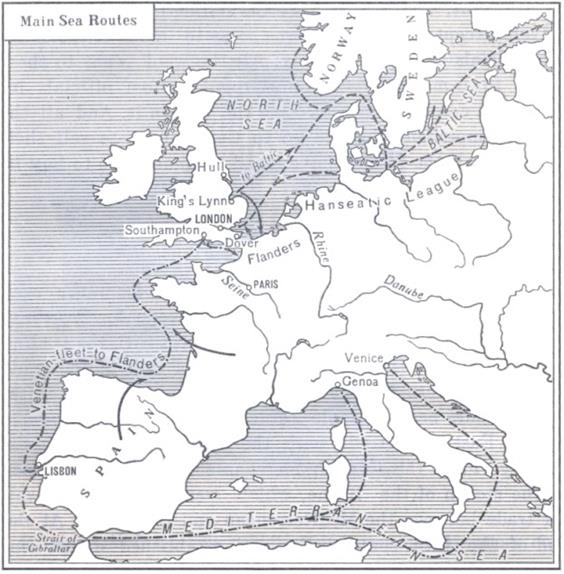

· European contacts

London merchants derived great incomes from trade with European countries, as London was one of the most important trading centres in Europe. It had commercial ties with the Mediterranean countries as well as the countries of Northern Europe. (See Map 8.) With the beginning of crusades the demand for oriental goods increased. Every year Venetian ships loaded with spices and silks sailed through the Straight of Gibraltar and up to the English Channel on their way to Flanders. But before they reached Flanders, they always called at ports on the southern coast of England. English merchants bought luxurious oriental goods and sold them again at a high profit. Particularly profitable was the trade in spices, which often cost their weight in gold.

As England traded with the Baltic and Scandinavian countries, an important sea route ran across the North Sea and the Baltic Sea. Hull, Boston, Dover, Newcastle, Ipswich had long been important trade centres.

The merchants of the Hanseatic League as well as traders from the Baltic states and Flanders settled in London, Hull and other English ports. Closer contacts with the Continent meant more goods available for exchange. In the 14th century, the list of imports was considerably increased. From France England imported wines, salt and building stone for castles and churches; a greater quantity and variety

Map 8

(From S.D. Zaitseva. Early Britain. Moscow, 1975.)

of cloths and spices was brought from the East. In its turn, England exported wool, tin, cattle and lead. At first, the bulk of the export trade was in the hands of the Venetian and Flemish merchants, but with the growth of trade at the beginning of the 14th century, more than half the trade fell into the hands of English merchants.

During the 14th century English merchants began to establish trading stations called ‘factories’ in different places in Europe. Often they replaced the old town guilds as powerful trading institutions. In 1363 a group of 26 English merchants who called themselves the Merchant Staplers, were granted the royal authority to export wool to the Continent through the French port of Calais. In return, they promised to lend money to English monarchs. The word ‘staple’ became an international term used by merchants to denote that certain goods could be sold only in particular places. Calais became the staple for English wool and defeated rival English factories in other foreign cities. The staple was a convenient arrangement for the established merchants, as it prevented competition and was a safe source of income for the Crown, which could tax exports more easily.

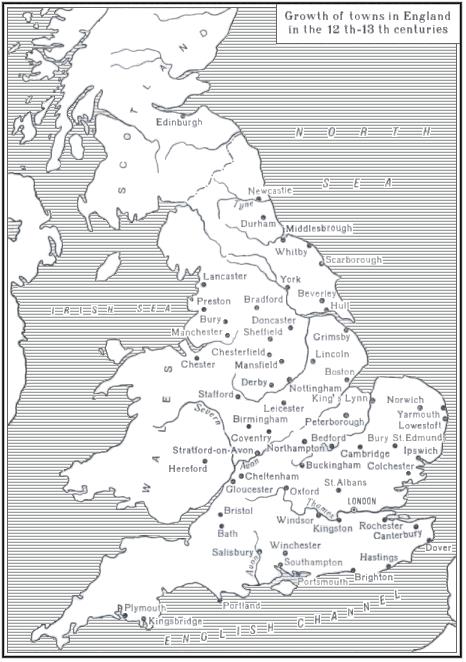

Growth of towns

· Free towns

The changes in the economic and social conditions were accompanied by the intermixture of people coming from different regions, the growth of towns with a mixed population, and the strengthening of social ties between the various regions.

The growth of trade promoted the growth of towns. (See Map 9) London, the residence of the Norman kings, became the most populous town of England. Two centuries before, kings had realised that towns could become effective centres of royal authority and balance the power of the local nobility. As a result, many towns got ‘charters of freedom’ which freed them from feudal duties to the local lord. These charters, however, had to be paid for, but they were worth the money. Towns could then raise their own taxes on coming goods. They could also have their own courts, controlled by the town merchants, on condition that they paid an annual tax to the king. People who lived inside the town walls were practically free from feudal rule. It was the beginning of a middle class and a capitalist economy.

Map 9

(From S.D. Zaitseva, Early Britain, Moscow, 1975.)

· Guilds

In towns, the central role was played by guilds. These were brotherhoods of merchants or artisans. The word ‘guild’ came from the Saxon word ‘gildan’ which meant ‘to pay’, as members of guilds had to pay towards the cost of the brotherhood. The right to form a guil

Дата добавления: 2021-01-11; просмотров: 610;