Origin of Climatic Change

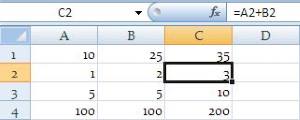

What causes climates to change? So many different factors influence climate that there is no shortage of possible explanations. One train of thought blames mankind for the temperature fluctuations of Fig. 5.13. The initial temperature rise is attributed to an increase in the carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere. Both the biologic and oceanic cycles are, on the average, balanced in their consumption and production of carbon dioxide. But there are also sources of carbon dioxide that have no absorption processes to counter their effects. The most significant of these sources is the burning of coal and

oil by man to produce heat for dwellings and mechanical energy for industry and transportation. At present our chimneys and exhaust pipes pour about 12 billion tons of carbon dioxide each year into the atmosphere, and this rate is rapidly increasing. Since 1880 the carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere has gone up by 12 percent (Fig. 5.14). Despite the relatively small proportion of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere—only 330 parts per million—it is a most significant constituent because of its ability to absorb solar energy reradiated by the earth and thus to contribute to the greenhouse effect that provides energy to the atmosphere.

The cooling of the atmosphere since 1945 must have a different explanation since the carbon dioxide content has continued to increase. The culprit here is thought by some scientists to be dust at high altitudes which scatters a portion of the incoming sunlight back into space. The chief natural source of airborne dust is volcanic eruptions. Man's contribution comes from the chimneys of industry, large-scale burning of tropical forests to clear land for agriculture, and soil particles blown away during mechanical cultivation. There is no question that a sufficiently large increase in atmospheric dust would lead to the observed general cooling of the atmosphere—but just how large an increase is needed and whether it has in fact occurred are not known, nor are the relative importances of the different dust sources.

Another point of view attributes climatic change to variations in the solar energy arriving at the top of the atmosphere, not to events within the atmosphere. (Of course, the carbon dioxide and dust contents of the atmosphere play a role in climate: the issue is which influences are primary and which are secondary.) The sun's radiation is not constant but fluctuates through the 11-year sunspot cycle, and a number of weather phenomena apparently follow a similar cycle. Perhaps there are long-term variations in solar output as well. Also, periodic changes in the earth's orbit bring it exceptionally close to and far from the sun from time to time. But does the radiation reaching the earth vary enough when this happens to produce the drastic climatic changes known to have taken place in the past, notably the ice ages? The puzzle of climatic change remains one of the most challenging in earth science.

Ocean Currents

The existence of different climates is due to the variation with latitude and season of the solar radiation arriving at the earth. This affects climate both directly, through the heating effect of the radiation, and indirectly, through the general circulation of the atmosphere that results. A secondary but nevertheless important element is the influence of the oceans.

The oceans affect climate in two ways. First, they act as reservoirs of heat which moderate the temperature extremes of the seasons. In spring and summer the oceans are cooler than the regions bordering them, since the heat they absorb is dissipated in a greater volume than in the case of solid, opaque land. The heat retained in the ocean depths means that in fall and winter the oceans are warmer than the regions bordering them. Heat flows readily between moving air and water; with a sufficient temperature difference, the rate of energy transfer from warm water to cold air (or from warm air to cold water) can exceed the rate at which solar energy arrives at the top of the atmosphere. With no such heat reservoir nearby, continental interiors experience lower winter temperatures and higher summer temperatures than those of coastal districts. In Canada, for instance, temperatures in the city of Victoria on the Pacific Coast range from an average January minimum of 36 °F to an average July maximum of 68 °F, whereas in Winnipeg, in the interior, the corresponding figures are — 8°F and 80°F.

Also influencing climate are surface drifts in the oceans produced by the friction of wind on water. Such drifts are much slower than movements in the atmosphere, with the fastest normal surface currents having speeds of about 7 mi/h.

The wind-impelled surface currents parallel to a large extent the major wind systems. The northeast and southeast trade winds drive water before them westward along the equator, forming the equatorial current. In the Atlantic Ocean this current runs head on into South America, in the Pacific into the East Indies. At each of these, points the current divides into two parts, one flowing south and the other north. Moving away from the equator along the continental margins, these currents at length come under the influence of the westerlies, which drive them eastward across the oceans. Thus gigantic whirlpools called gyres are set up in both Atlantic and Pacific Oceans on either side of the equator. Many complexities are produced in the four great gyres by islands, continental projections, and undersea mountains and valleys.

Currents also occur deep in the ocean, though their speeds are usually slower than those of surface currents. In the polar regions of both hemispheres cold water sinks because of its greater density and flows toward the equator several miles below the surface. These cold currents keep tropical waters cooler than they otherwise would be, and they also bring oxygen to the lower depths of the ocean which enables plant and animal life to occur there.

Thus the oceans, besides acting as water reservoirs for the earth's atmosphere, play a direct part in temperature control—both by preventing abrupt temperature changes in lands along their borders and by aiding the winds, through the motion of ocean currents, in their distribution of heat and cold over the surface of the earth.

Дата добавления: 2021-10-28; просмотров: 873;