The Temple of Solomon

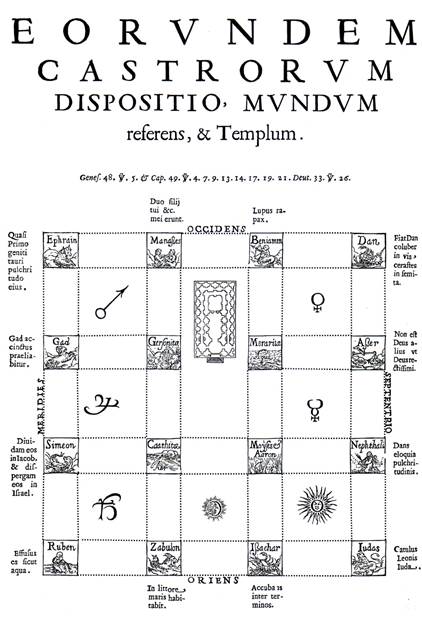

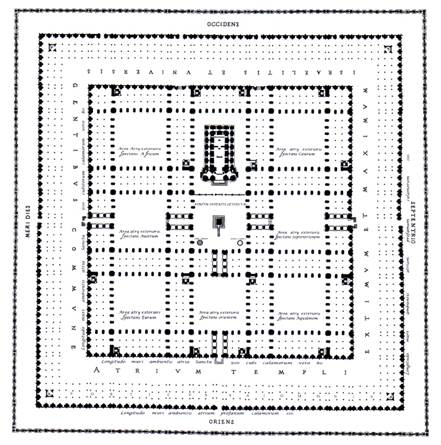

Newton’s interest in the Temple was not an isolated one. Reconstructions of the Temple of Solomon were ubiquitous by the end of the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th century. There had been major reconstructions of the Temple; for example, the 12th century Jewish philosopher Rabbi Moses Maimonides (Lewittes: 1957) and 13th century theologian Nicholas of Lyra (Smith et al: 2012). However, the first significant reconstruction that stimulated the imagination of theologians, architects and the general public was architect and Jesuit priest Juan Battista Villalpando’s In Ezechielem Explanationes et Apparatus Vrbis Templi Hierosolymitani published in 1604 (Villalpando: 1604). It was a three volume Scriptural exegesis of the Book of Ezekiel. The entire second volume was a reconstruction of Ezekiel’s vision of the Temple of Jerusalem, which Villalpando claimed was a vision of the Temple of Solomon. Ezechielem Explanationes is elaborately illustrated with some of the engravings folding out to over a metre in width. The plan of the Temple was square, symmetrical and was laid out to a celestial plan and built to musical, therefore divine, proportions (see Figure 1 and 2) – the plan was the microcosm of the macrocosm (Morrison: 2008).

With the notoriety of Villalpando’s work came both support and criticism for his reconstruction. There were six main points of debate stimulated by Ezechielem Explanationes. First, the Divine origins of the Temple were questioned: was God the architect of the Temple? If it was a God-given plan, did the Temple constitute the origins of architecture? Second, Villalpando’s reconstruction had no historic basis. It was far too elaborate for the tenth century BC and it would not have been built in the classical style. Third, the Temple’s architecture was not the pinnacle of architecture and the design would be surpassed by subsequent designs, in particular Herod’s Temple which was larger and grander than Solomon’s Temple. Fourth, the interpretation of the Biblical measurements, the sacred cubit, by Villalpando was wrong and the result of this was that Villalpando’s plan exceeded the site of the Temple at Mount Morion. Fifth, there was a lack of Jewish sources in Villalpando’s work, such as the Torah and the works of Maimonides. Finally Ezekiel’s vision of the Temple was not the same as the Temple of Solomon. It was the last two points regarding the sources of the Temple that generated the most criticism and generated a large number of reconstructions in response. The sources of the reconstructions were the Book of Ezekiel, the Book of Kings or Torah. Many of these reconstructions were published,[i] some were built as scale models and some remained unpublished.

Figure 1: Villalpando’s plan of the Temple as microcosm of the universe (Drawn by the author from (Villalpando and Prado: 1604, 470)).

Figure 2: Villalpando’s floor plan of the Temple of Solomon (Drawn by the author from (Villalpando and Prado: 1604, unpaginated)).

There was a great deal of diversity in the reconstructions of the Temple of Solomon in the seventeenth and eighteenth century which derived from the debate on the plan of the Temple. At first the debate appears to be a continental European debate. However, there were English reconstructions. Non-conformist minister and natural philosopher, Samuel Lee published Orbis miraculum, or, The temple of Solomon pourtraied by Scripture-light in 1659 with a second edition in 1665. There were also unpublished reconstructions such as Newton’s Prolegomena ad Lexici Propretici partem Secundam: De Forma Sanctuary Judaici (Babson Ms 434), and William Stukeley’s manuscript entitled The Creation, Music of the Spheres K[ing] S[olomon’s] Temple Microco[sm] - and Macrocosm Compared &C written between 1721-24. There was not a theological divide between Protestant and Catholic; it was architectural criticism. In fact Villalpando was praised. Lee claimed that Villalpando was “the learned and worth publishers of the splendid work” and he was “the most learned and laborious student, that ever proceeded into public light”, who has unravelled “the profound and mysterious visions of the Prophet Ezekiel (Lee: 1659, unpaginated)”. In Newton’s unpublished manuscripts he mixed praise and criticism and he claimed that “Villalpando, although the best [and] the most eminent commentator on Ezekiel’s Temple: yet [he is] out in many things (Newton: undated, 32v).” He also claimed that the Villalpanda’s reconstruction was a “fantasy” that was “lacking in reason (Newton: 2011, 155).” While Stukeley claimed that Villalpando was

the learned Spaniard… we can never illustrate architecture so well as by strictly considering this completest work & most perfect example of all others, of whose measures & forms throughout description in very different places of the holy scripture we can never illustrate architecture so well as by strictly considering this completest work & most perfect example of all others, of whose measures & forms throughout description in very different places of the holy scripture (Stukeley: 1721 – 24, 73).

Despite his praise, Stukeley believed that Villalpando had not “hit the white” and he reconstructed the Temple to a far more modest design.

There was also a public face to this debate in England, which outweighed the theological and academic debate. Two exhibitions of architectural models of the Temple were displayed in London in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, to great acclaim (anonymous: 1724a, 1724b & 1725). The first was created by Rabbi Jacob Judah Leon from Amsterdam whose model came to London between 1675 and 1680, and reappeared in 1778. The second was a model that was commissioned by Gerhard Schott from Hamburg and was exhibited in London between 1724 and 1731. The Schott model was built to the plan of Villalpando’s interpretation of the Book of Ezekiel while the Leon model was built to the plans preserved in Jewish sacred texts. The Schott model remained in London over the seven years with exhibition, and although it is not known exactly how long the Leon model remained in London contemporary reports claim that it was “commonly to be seen in London (Shane: 1983).”

These two architectural models drew large crowds who paid to see the models, when the Schott model exhibition first opened it cost a staggering half guinea entrance fee (Anonymous: 1724a, 2). In addition, guidebooks of the Temple were sold at both the Leon and Schott exhibitions (Leon: 1675; Anonymous: 1725). Broadsheets of the Temple were also sold at the Leon exhibition. (Offenberg: 1994). Some surviving guide-books have images of other reconstructions bound up with them,[ii] revealing that the viewer was not just satisfied with the one reconstruction. Their amazing popularity was a phenomenon of the time.

It was in the late 1670s when the Leon model was in London that Newton’s interest in Solomon’s Temple begun. Newton does not mention Leon or his Temple; however, there was a heightened awareness and interest in the Temple of Solomon at this time at all levels of society.

When the Schott model arrived in London in 1724 Newton lived in central London. Both the Leon and Schott models could have stimulated Newton’s interest in the Temple, but he would not have agreed with either one. The Schott model was built to the plan of Villalpando, a plan that Newton disagreed with. He pointed out that, although Villalpando’s main source was the Book of Ezekiel, his gridded-plan contradicted some of the main features that Ezekiel described. At the same time Newton strongly agreed with Villalpando’s rational and theological underpinnings, which saw the Temple as the microcosm of the macrocosm. At Christmas time 1725, Stukeley and Newton discussed their respective plans of the Temple of Solomon (Stukeley: 1936, 18), and it does seem inconceivable that they did not discuss the Schott model, given the fanfare that it had received in the year when it had arrived in London, and its ongoing exhibition.

Within twenty months of the Schott model arriving in London, William Whiston, former pupil and successor to Newton as Lucasian Professor at Cambridge, “has made a model of the Temple to show in opposition to that in the Haymarket (Anonymous: 1726, 2).” How detailed, or how large, the model was is unknown, since neither the model nor any plans or drawings have survived. However, the reporter seems to find the challenge to the Schott model exasperating, since he claimed that both models “pretended to be true models, yet are different. If our virtuosos can’t agree upon corporeals, no wonder there is such a different in speculative matters (Anonymous: 1726, 2).”

The Leon and the Schott exhibitions were not the only exhibitions on the Temple of Solomon. A later model was built by Christoph Semler in 1718, this model never left Halle, Germany as it was housed in a school and was used as a teaching aid (Whitmer: 2010). While it was viewed by the community and was a significant part of that community, it did not have any impact outside of Halle. However, the Leon and Schott models travelled and were on exhibition for a relatively long time, and both were housed in public exhibition spaces for maximum exposure. These exhibitions were unique and were viewed by Royalty, the gentry, the scientific community and the general public.

Дата добавления: 2016-07-27; просмотров: 2238;