Approaches to classification of parts of speech

These, and a number of other problems, made linguists search for alternative ways to classify lexical units. Some of them suggested that the contradictions should be settled if parts of speech were classified a unified basis of subdivision; in other words, if a homogeneous, or monodifferential classification of parts of speech were undertaken. It must be noted that the idea was not entirely new. The first classification of parts of speech was homogeneous: in ancient Greek grammar the words were subdivided mainly on the basis of their formal properties into changeable and unchangeable; nouns, adjectives and numerals were treated jointly as a big class of “names” because they shared the same morphological forms. This classical linguistic tradition was followed by the first English grammars: Henry Sweet divided all the words in English into “declinables” and “indeclinables”. But the approach which worked well for the description of highly inflectional languages turned out to be less efficient for the description of other languages.

The syntactic approach, which establishes the word classes in accord with their functional characteristics, is more universal and applicable to languages of different morphological types. The principles of a monodifferential syntactico-distributional classification of words in English were developed by the representatives of American Descriptive Linguistics, L. Bloomfield, Z. Harris and Ch. Fries. Ch. Fries selected the most widely used grammatical constructions and used them as substitution frames: the frames were parsed into parts, or positions, each of them got a separate number, and then Ch. Fries conducted a series of substitution tests to find out what words can be used in each of the positions. Some of the frames were as follows: The concert was good (always). The clerk remembered the tax (suddenly). The team went there. All the words that can be used in place of the article made one group, the ones that could be used instead of the word “clerk” another, etc. The results of his experiments were surprisingly similar to the traditional classification of parts of speech: he distinguished four major classes of what he called “positional words” (or “form-words”) – the words which can be used in four major syntactic positions without affecting the meaning of the structures; generally speaking, these classes coincide with the four major notional parts of speech in the traditional classification: nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs. Besides, Ch. Fries distinguished 15 limited groups of words, which cannot fill in the positions in the frames. These “function words” are practically the same as the functional words in the traditional classification.

So, the syntactico-distributional classification of words distinguished on a syntactic basis testifies to the objective nature of the traditional classification of parts of speech. More than that, in some respects the results of this approach turn out to be even more confusing than the allegedly “non-scientific” traditional classification: for example, one word might be found in different distributional classes. Thus, the syntactico-distributional classification cannot replace the traditional classification of parts of speech, but the major features of different classes of words revealed in syntactico-distributional classification can be used as an important supplement to the traditional classification.

The combination of syntactico-distributional and traditional approaches proves the unconditional subdivision of the lexicon into two major supra-classes: notional and functional words. The major formal grammatical feature of this subdivision is their open or closed character. The notional parts of speech are open classes of words, with established basic semantic, formal and functional characteristics. There are only four notional classes of words, which correlate with the four main syntactic positions in the sentence: nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. They are interconnected by the four stages of the lexical derivational paradigm, e.g.: to decide – decision – decisive – decisively. The functional words are closed classes or words: they cannot be further enlarged and are given by lists. The functional words expose various constructional functions of syntactic units, and this makes them closer to grammatical rather than to lexical means of the language. As for pronouns and the numerals, according to the functional approach they form a separate supra-class of substitutional parts of speech, since they have no function of their own in the sentence, but substitute for notional parts of speech. The difference between the four notional parts of speech and substitutional parts of speech is also supported by the fact that the latter are closed groups of words like functional parts of speech. The three supra-classes are further subdivided into classes (the parts of speech proper) and sub-classes (groups inside the parts of speech).

Another advanced approach which also helps clarify many disputable points in the traditional classification of parts of speech, is connected with the implementation of the linguistic field theory to the parts of speech classification. It was formulated by the Russian linguists G. S. Schur and V. G. Admoni. According to this approach, the borderlines between the classes of words are not rigid; instead of borderlines there is a continuum of numerous intermediary phenomena, combining the features of two or more major classes of words. Field theory states that in each class of words there is a core, the bulk of its members that possess all the characteristic features of the class, and a periphery (marginal part), which includes the words of mixed, dubious character, intermediary between this class and other classes of words. For example, the non-finite forms of the verb (the infinitive, the gerund, participles I and II) make up the periphery of the verbal class: they lack some of the features of a verb, but possess certain features characteristic to either nouns, or adjectives, or adverbs.

These are the major advanced linguistic approaches, which supplement and significantly improve the traditional classification of word classes.

Controversial aspects of the English noun and verb

English noun

The noun in English distinguishes the following grammatical categories: the category of number, case, gender, and article determination. The basic problems with the interpretation of the noun are caused by typological restructuring of the English language, which led to the extinction of most inflectional noun forms and the reduction of noun paradigms in the history of English. The two most controversial categories of the noun in modern English are the category of case and the category of gender.

As for the category of case, linguists argue, first, whether the category of case still exists in modern English, and, second, if it does exist, how many case forms of the noun can be distinguished in English. In the analysis of this problem, four different approaches can be outlined.

The approach which is usually defined as “the theory of positional cases” was developed by J. C. Nesfield, M. Deutchbein, M. Bryant and other linguists. They follow the patterns of classical Latin grammar, distinguishing nominative, genitive, dative, accusative and vocative cases in English. Since there are no special morphological marks to distinguish these cases in English (except for the genitive) like in Latin or other inflectional languages, the cases are differentiated by the functional position of the noun in the sentence, e.g.: the nominative case corresponds with the subject, the accusative case with the direct object, the dative case with indirect object, and the vocative case with the address. Thus, “the theory of positional cases” presents an obvious confusion of the formal, morphological characteristics of the noun and its functional, syntactic features. This approach only shows that the grammatical meanings expressed by case forms in inflectional languages (“noun-declensional” languages) are regularly expressed in English by other means, in particular by syntactic positions, or word-order.

The approach which is defined as “the theory of prepositional cases” supplements the previous approach and follows the same route of Latin-oriented grammar traditions. The linguists who formulated it, G. Curme among them, treat the combinations of nouns with prepositions as specific analytical case forms, e.g.: the dative case is expressed by nouns with the prepositions ‘to’ and ‘for’, the genitive case by nouns with the preposition ‘of’, the instrumental case by nouns with the preposition ‘with’, e.g.: for the girl, of the girl, with a key. They see the system of cases in English as comprising the regular inflectional case (the genitive), “positional cases”, and “prepositional cases”. This approach is not recognized by mainstream linguistics either, because, again, syntactical and morphological characteristics of the noun are confused. Besides, as B. Ilyish noted, if to be consistent in applying this theory, each prepositional phrase should be considered as a separate case form and their number will be almost infinite.

The approach which can be defined as “the theory of limited case” is the most widely accepted theory of case in English today. It was formulated by H. Sweet, O. Jespersen and further developed by Russian linguists A. Smirnitsky, L. Barchudarov and others. It is based on the oppositional presentation of the category: the form defined as “the genitive case” is the strong member of the opposition, marked by the postpositional element ‘–s’ after an apostrophe in the singular and just an apostrophe in the plural, e.g.: the girl’s books, the girls’ books; the genitive is opposed to the unfeatured form, the weak member of the opposition, which is usually referred to as “the common case” (“non-genitive”). The category of case is realized in full in animate nouns and restrictedly in inanimate nouns in English, hence the name – “the theory of limited case”. Besides being semantically (lexically) limited, the category of case in English is limited syntactically, as the genitive case form of the noun is used only as an attribute, and it is also positionally limited: it is used predominantly in preposition to the word it modifies (except for some contexts, known as “double genitive”, e.g.: this idea of Tom’s).

The approach which can be defined as “the theory of the possessive postposition”, or “the theory of no case” states that the category of case did exist in Old English, but was completely lost by the noun in the course of its historical development. The proponents of this theory, G. N. Vorontsova, A. M. Mukhin among them, maintain that what is traditionally treated as the inflectional genitive case form is actually a combination of the noun with a postposition denoting possession. The main arguments to support this point of view are as follows: first, the postpositional element ‘s is not only used with words, but also with the units larger than the word, with word-combinations and even sentences, e.g.: his daughter Mary’s arrival, the man I saw yesterday’s face; it may be used with no noun at all, but with a pronoun, e.g.: somebody else’s car; second, the same meaning of possession is rendered in English by prepositional of-phrases, e.g.: this man’s daughter – the daughter of this man. The followers of this approach conclude that –s is no longer an inflection, but a particle-like postpositional word, so, “noun +–‘s” is not a morphological form of the noun, but a purely syntactical construction and there is no longer a morphological category of case in English.

The advocates of “the possessive postpositive theory” have managed to specify the peculiarities of the genitive in English which make it different from regular case forms in inflectional languages; still, there are certain counter-arguments that prove the existence of the case category in English. First, cases when the possessive postpositive –‘s is added to units larger than the word are very few in comparison to cases where it is added to the noun (some estimates show the correlation as 4% to 96% respectively), besides, these cases are often stylistically marked and most of them make intermediary phenomena between a word and a word-combination, e.g.: what-his-name’s hat; the same applies to the use of the genitive marker –‘s with certain pronouns. Second, the possessive postpositive differs from regular particles: regular postpositional particles usually correspond with prepositions (to give up – up the hill), which is not the case with –‘s; the combinations of words with postpositional particles are usually lexicalized and recorded in dictionaries, while – ‘s is grammatically bound to the use of the noun and their combinations are never recorded as separate lexical units; –‘s is phonetically close to regular morphemes, as it has the same variants distinguished in complementary distributions as the grammatical suffix –s: [-s], [-z], [-iz]; thus, actually the status of –‘s is intermediary between a particle and a morpheme. As for the semantic parallelism between possessive postpositional constructions and prepositional of-phrases, there are definite semantic differences between them in most contexts: for example, as has been mentioned, genitive case forms are predominantly used with animate nouns, while of-phrases are used with inanimate nouns.

The solution to the problem of the category of case in English can be formulated on the basis of the two theories, “the theory of limited case” and “the theory of the possessive postpositive”, critically revised and combined. There is no doubt that the inflectional case of the noun in English has ceased to exist. The predominantly particle nature of the –‘s-marker is evident, but this does not prove the absence of the category of case: it is a specific particle expression of case which can be likened to the particle expression of the category of mood in Russian, cf.: Я бы пошел с тобой. Besides, two subtypes of the genitive are to be recognized in English: the word genitive (the principal type) and the phrase genitive (the minor type).

The category of gender is another highly controversial subject in English grammar. The majority of linguists stick to the opinion that the category of gender existed only in Old English. They claim that, since formal gender marks disappeared by the end of the Middle English period and nouns no longer agree in gender with adjectives or verbs, there is no grammatical category of gender in modern English. They maintain that in modern English, the biological division of masculine and feminine genders is rendered only by lexical means: special words and lexical affixes, e.g.: man – woman, tiger – tigress, he-goat – she-goat, male nurse, etc.

The fact is, the category of gender in English differs from the category of gender in many other languages, for example, in Russian or in German. The fact is, the category of gender linguistically may be either meaningful (or, natural), rendering the actual sex-based features of the referents, or formal (arbitrary). In Russian and some other languages the category of gender is meaningful only for human (person) nouns, but for the non-human (non-person) nouns it is formal; i.e., it does not correspond with the actual biological sense. In English gender is a meaningful category for the whole class of the nouns, because it reflects the real gender attributes (or their absence/ irrelevance) of the referent denoted. It is realized through obligatory correspondence of every noun with the 3rd person singular pronouns - he, she, or it: man – he, woman – she, tree, dog – it. For example: A woman was standing on the platform. She was wearing a hat. It was decorated with ribbons and flowers… Personal pronouns are grammatical gender classifiers in English.

The existence of the category of gender can be proved in the contexts of grammatical transposition, when the weak member of the opposition, nouns of the neuter gender, are used as if they denote female or male beings, substituted by the pronouns ‘he’ or ‘she’. In most cases such use is stylistically colored. It is known as the stylistic device of personification and takes place either in some traditionally fixed contexts, e.g.: a vessel – she; or in high-flown speech, e.g., Britain – she, the sea – she.

Thus, the English language has preserved the basic grammatical categories of the noun, including the categories of case and gender, though their means of expression have been considerably transformed and are no longer inflectional, which causes a lot of controversy in their treatment.

English verb

The verb in English distinguishes the following categories: the category of person and number, tense, aspect, voice and mood. The basic problems with the interpretation of verbal forms are caused by typological restructuring of the English language, which has led to the extinction of most inflectional verbal forms, the appearance of new analytical forms, reduction of and confusion in verbal paradigms in the history of English.

The most controversial are the categories of tense and aspect. The major problem is the fusion of temporal and aspectual semantics and the blend in their formal expression; that is why in practical grammar they are traditionally treated not as separate verbal forms but as specific tense-aspect forms, cf.: the present continuous – I am working; the past perfect continuous – I had been working; the future indefinite – I will work, etc.

In theoretical grammar the two categories are treated separately, but still, there is a lot of dispute among linguists. As for the category of tense, the problem is that there are not just three tense forms of the verb like in Russian – the past, the present and the future, but four forms – the past, the present, the future and the future-in-the-past (ate – eat – will eat – would eat). The future-in-the-past is particularly controversial from the point of view of its theoretical interpretation, because, logically speaking, one and the same category cannot be expressed twice in one and the same grammatical form; the members of one paradigm should be mutually exclusive. Some linguists, O. Jespersen and L. S. Barkhudarov among them, go as far as to state the there is no future tense in English at all. They claim that the verbs shall/will and should/would are not auxiliary verbs, but modal verbs denoting intention, command, request, promise, etc. in a weakened form, e.g.: I’ll go there by train means I intend (want, plan) to go there by train.

Some of the controversies can be tackled if verbal categories are treated oppositionally on the basis of their functional semantics. Semantically, tense, as the grammatical expression of time, may be either oriented toward the moment of speech, “absolutive”, or it may be “relative”, when it shows the correlation of two or more events. The “absolute time” includes the past, the present and the future; the “relative time” includes the priority, the simultaneity and the posteriority. The present and the past forms of the verb in English render absolutive time semantics, referring the events to either the plane of the present or to the plane of the past, while the two future tense forms of the verb express relative future: they present the process as an after-event in relation to the present, e.g.: He will work tomorrow (not right not), and as an after-event in relation to the past, e.g.: He said he would work the next day. So, according to the approach formulated by professor Blokh, there is not just one verbal category of tense in English but two interconnected tense sub-categories: the first, which can be called “primary time”, “absolutive time”, or “retrospective time”, is expressed by the opposition of the past and the present forms (e.g.: work-worked); the second, which may be called “prospective”, or “relative”, is formed by the opposition of the future and the non-future separately in relation to the present or to the past (e.g.: work(s) - shall/will work, or worked - should/would work).

As for the aspect, the analysis of this category has always been a highly controversial area of English linguistics: the four aspective forms of the verb - the indefinite, the continuous, the perfect, and the perfect continuous - have been treated by different scholars as tense forms, as aspect forms, as forms of mixed tense-aspect status, and as neither tense nor aspect forms, but as forms of a separate grammatical category.

For example, the grammatical meaning of the continuous was originally treated as a tense form, denoting a process going on simultaneously with another process; this temporal interpretation was developed by H. Sweet, O. Jespersen and others. The majority of linguists today support the point of view developed by A. I. Smirnitsky, B. A. Ilyish, L. S. Barkhudarov, and others, that the meaning of the continuous is purely aspective, denoting “action in progress”, or “developing action”. The fact is, simultaneity is rendered by either the syntactic construction or the broader semantic context, since it is quite natural for the developing action to be connected with a certain time point. Actually, simultaneous actions can be shown with or without the help of the continuous verbal forms, cf.: While I worked, they were speaking with each other. – While I worked, they spoke with each other.

The traditional treatment of the perfect was also primarily as the tense form denoting the priority of one action in relation to another; the so-called “perfect tense” interpretation was developed by H. Sweet, G. Curme, and others. M. Deutchbein, G. N. Vorontsova and other linguists consider the perfect to be a purely aspective form, laying the main emphasis on the fact that the perfect forms denote some result, some transmission of the pre-event to the post-event. A. I. Smirnitsky was the first to put forward the idea that the perfect forms its own category, which is neither a tense category, nor an aspect category; he suggested the name “the category of time correlation”.

According to professor Blokh’s approach, this contradiction can be solved in exactly the same way that was employed with the tense category: the category of aspect, just like the category of tense, is not a unique grammatical category in English, but a system of two sub-categories. The first sub-category is realized through the paradigmatic opposition of the continuous (progressive) forms and the non-continuous (indefinite, simple) forms of the verb; this category can be called the category of development. The second aspective sub-category is formed by the opposition of the perfect and the non-perfect forms of the verb; this category can be called “the category of retrospective coordination”. This sub-category is semantically intermediate between aspective and temporal, because the perfect combines the meanings of priority (relative time) and coordination, transmission, or result (aspective meaning).

Another verbal category which has given rise to much dispute is the category of mood in English. The oblique mood types, denoting unreality of action, presents a great problem because most of its forms are homonymous with the forms of the indicative, denoting real actions. Different classifications of the oblique mood types are based either on formal criteria or on functional criteria: scholars distinguish synthetical and analytical moods (e.g.: If I were you… - synthetical mood, … I would stay – analytical mood), past and present moods (e.g.: I wish I stayed – I demand that he stay); semantically the so-called imperative, subjunctive, conditional and suppositional moods are distinguished. Today, there is no universally accepted classification of verbal mood forms; their number varies from as many as sixteen (in the classification of M. Deutschbein) to practically no mood at all (according to L. S. Barkhudarov).

According to professor Blokh’s approach, since all the oblique mood types share a common meaning of unreality, they may be terminologically united as subjunctive; and then several types of the subjunctive can be distinguished according to the form of expression and various shades of unreality expressed. The mood which is traditionally called subjunctive I, expresses various attitudes of the speaker: desire, consideration (supposition, suggestion, hypothesis), inducement (recommendation, request, command, order), etc. The form of subjunctive I is homonymous with the bare infinitive: Long live the king! I demand that the case be investigated thoroughly. Subjunctive II in form is homonymous with the past tense forms of the verbs in the indicative mood, except for the verb to be, which, according to standard grammar, in all persons and numbers is used in the form were. Subjunctive II is used mostly in the subordinate clauses of complex sentences with causal-conditional relations, such as the clauses of unreal condition, e.g.: If she tried, (she would manage it); If I were you…; and a number of related meanings, for example, of urgency, e.g.: (It’s high time) she tried to change the situation; or of unreal wish, e.g.: (I wish) she tried harder; If only she tried! Subjunctive III (traditionally known as the “conditional”) denotes the corresponding consequence of an unreal condition in the principal part of the causal-conditional sentences; in form it is homonymous with the analytical future in the past tense forms (the past posterior) of verbs in the indicative mood, e.g.: (If she tried), she would manage it. Subjunctive IV (traditionally referred to as “modal suppositional”) is built with the help of modal verbs, and expresses the same semantic types of unreality as subjunctive I, cf.: may/might + infinitive – is used to denote wish, desire, hope, and supposition, e.g.: May it be so! (cf. with subjunctive I: Be it so!); should + infinitive, e.g.: Whatever my mother should say about him, we’ll marry one day (cf. with subjunctive I: Whatever my mother say about him, we’ll marry one day).

In traditional grammar, besides the direct and oblique moods, the so-called imperative mood is distinguished, as in Open the door! or Let’s agree to differ; Let him do it his own way! The analysis of such examples shows that there is basically no difference between what is traditionally called the imperative and subjunctive I for the 2nd person or subjunctive IV for the other persons: the meaning rendered by the so-called imperative is that of a hypothetical action appraised as an object of desire, recommendation, supposition, etc. and its forms are homonymous either with the bare infinitive or the constructions with the semi-notional verb “to let”. Thus, inducement can be treated as a specific type of unreality and the imperative mood can be treated as a subtype of subjunctive I or subjunctive IV. It can be noted that L. S. Barkhudarov, who denied the existence of the oblique moods in English, treated subjunctive I, vice versa, as a subtype of the imperative.

English phrase

The problem of the definition of the phrase. F.F. Fortunatov, A.A.Shahmatov and A.M.Peshkovski started the theory of the phrase (end XIX-beginning XX century) they consider any syntactical group of words to be a phrase, they didn’t take into account the meaning of such groups. Beginning from 50th of XX century V.V.Vinogradov narrowed this definition. The phrase was considered to be any syntactical group of notional words, agreed with each other (subordination). The coordinate and the predicative connection of words were excluded from the theory of phrase. At present, Phrase is considered to be everycombination of two or more words, which are a grammatical unit but not an analytical form of some word. The phrase may denote:

- A concrete thing, e.g.: “A little winding path led them to the river” (W.S.Maugham)

- An action, e.g.: “Here.’I said. ‘You’re soaked. Come and have a drink.” (V.S.Pritchett)

- A quality, e.g.: “It at once struck him that her hair was almost identical in color with sand, so incredibly fine and sun-bleached that it was almost white.” (H.E.Bates)

- A whole situation, e.g.: “it’s from a man who wants you to investigate the disappearance of his wife’s Pekinese dog” (A.Christie). The underlined phrase may be transferred into a sentence – “His wife’s Pekinese dog disappeared”.

The phrase may consist of:

- Notional words alone, which have a very clearly pronounced self-dependent nominative destination, e.g.: He held a small pickled onion delicately on the end of his fork. (S.Hill)

- Notional and functional words, these combinations are stamped, e.g.: “It is to some extent seasonal work” (S.Hill). She turned and looked at Guy. (W.S.Maugham), the words “some, extent; looked” are notional, the words “to; at” are functional.

- Only functional words, used as connectors and specifiers of notional elements of various status “so that”, “out of”, “up to”, “such as”, etc., e.g.: “I like a bit of singing and dancing, it cheers you up, Esme, it takes you out of yourself” (S.Hill)

The phrase may perform different functions in a sentence

a) Subject, e.g.: “To hurt a boy would have been nothing” (J.Wain)

b) Predicate, e.g.: “I don’t give much thought to it” (J.Wain)

c) Object, e.g.: I wanted him to be free and happy (V.S.Pritchett)

d) Attribute, e.g.: There was a man in an allotment who had asked him for a light and wanted to know his business. (V.S.Pritchett)

e) Adverbial modifier, e.g.: He sat and waited, his eyes cast down shyly (W.S.Maugham).

The features of the phrase: 1. It is a nominative unit. 2. It is a unit of language. 3. It is a part of a sentence. 4. It isn’t a communicative unit. 5. It isn’t intonationally marked.

The syntactic bond is a syntactical relation between the components of a phrase. There are two theories concerning the types of syntactic bond.

1. Professor B.Ilyish distinguishes two main syntactical relations between the components of a phrase: Agreement and government. Agreement is a method of expressing a syntactical relationship, which consists of making a subordinate word take a form similar to that of the word to which it is subordinate, e.g.: this word, these words. Government – is the use of a certain form of the subordinate word required by its head, but not coinciding with the form of the head word itself, e.g.: find him, invite her.

2. L.S.Barhudarov, M.Y.Blokh, I.P.Ivanova, G.G.Pocheptsov and other our scholars distinguish three main types of the syntactic bonds – coordination, subordination and predication.

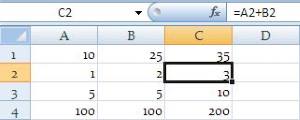

3. Blokh M.Y. distinguishes one more type – cumulation (see the table attached)

Дата добавления: 2020-03-17; просмотров: 3930;