Hydrothermal features

Yellowstone contains a great variety of strange and wonderful hydrothermal features including geysers, hot springs, fumaroles, mudpots and mud volcanoes. Of these, geysers are the most impressive, and no trip to the park is complete without a visit to Old Faithful, Yellowstone's most reliable geyser. It is not the largest of Yellowstone's geysers, but it does erupt to heights over 30 m every 80 minutes or so giving tourists a guaranteed photo opportunity. There are other smaller geysers that erupt more frequently, and some larger geysers that only erupt once every several days.

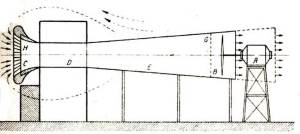

There are more geysers at Yellowstone (over 500, located in seven geyser basins) than in all the other hydrothermal regions of the world put together. Geysers are so abundant in Yellowstone because of a combination of plenty of precipitation, porous, fractured rocks and a heat source from the body of magma beneath. When water from rainfall or melting snow percolates deep enough into the bedrock, it becomes so hot that it is forced back upwards through cracks and joints in the rock. In some places the rising hot water fills a void in the rock (a chamber) with a constricted opening to the surface.

In these places the rising water fills the chamber more quickly than it can escape upwards, eventually causing the pressure to build up to such an extent that superheated water explodes into steam, blasting upwards through the constricted passage to the surface as a geyser eruption. After the geyser has erupted, it remains dormant until the underground chamber has refilled and the critical pressure is again reached.

The size and frequency of geyser eruptions depend upon many factors including the size and configuration of the chamber, the rate of water movement through the rock, and the size and length of fractures in the rock that connect chambers with each other and with the surface. All of this can be thought of as the underground 'plumbing' of a geyser. Like Old Faithful, some geysers are remarkably regular, but it only takes a minor earthquake to shift the underground plumbing and change their character and timing. The geyser basins of Yellowstone are dynamic, ever adjusting to movements in the crust that cause some geysers to go extinct while new ones are born.

Hot springs are far more common than geysers occurring wherever heated ground-water rises gently to the surface. Points where only steam reaches the surface are called fumaroles. The hot springs of Yellowstone are highly varied in size, temperature and colour. The colours depend on differences in the temperature and chemical composition of the water and the presence of species of algae and bacteria adapted to those conditions.

A hot spring can also be distinctive for the rim of mineral deposits that builds up around it. As the rising groundwater spills out over the surface, silica in solution precipitates to form whitish deposits of sinter. This not only forms the rim of pools but can build up into mounds or cones where geysers erupt, and can form large, whitish expanses as at Porcelain Basin. In areas of Yellowstone underlain by limestone, such as at Mammoth Hot Springs, travertine rather than sinter is deposited around the springs.

In some parts of Yellowstone the ground-water is very acidic due to hydrogen sulphide gas from the crust mixing with water and being metabolised by bacteria to produce sulphuric acid. One of the most acidic springs in the park is Sulphur Caldron. Here the water has a pH of just 1.2 – and a foul, sulphurous smell of rotten eggs. It is not a place where tourists linger long! In such areas, silica compounds stay in solution and there is no deposition of sinter. Instead, surrounding rocks are chemically weathered into clays, and where the hot, acidic ground-water rises to the surface it often forms viscous, bubbling pools of mud known as mudpots. Sometimes the mud can pile up into a cone as at Mud Volcano, only to be blown away in a muddy eruption once there is enough steam pressure.

Дата добавления: 2021-10-28; просмотров: 462;