QUESTIONS AND ASSIGNMENTS

1. Explain why linguistic changes are usually slow and gradual.

2. At first glance the vocabulary of the language seems to change very rapidly, as new words spring up all the time. Could the following words be regarded as absolutely new? (Note the meaning, component parts and word-building pattern); jet-plane (cf. airplane), typescript (cf. manuscript), air-lift, baby-sitter, sputnik, Soviet, safari, bestseller, cyclization, air-taxi, astrobiology, sunsuit, pepper, gas.

3. In the 14th c. the following words were pronounced exactly as they are spelt, the Latin letters retaining their original sound values. Show the phonetic changes since the 14th c: moon, fat, meet, rider, want, knee, turn, first, part, for, often, e.g. nut — [nut] > [nʌt].

4. Point out the peculiarities in grammatical forms in the following passages from Shakespeare's SONNETS and describe the changes which must have occurred after the 17th c:

a) As fast as thou shalt wane, so fast thou grow'st

In one of thine, from that which thou departest ...

b) It is thy spirit that thou send'st from thee ...

It is my love that keeps mine eyes awake;

Mine own true love that doth my rest defeat —

c) Bring me within the level of your frown.

But shoot not at me in your wakened hate!

5. Comment on the following quotations from the works of prominent modern linguists and speak on the problems of linguistic change:

a) One may say with R. Jakobson, a little paradoxically, that a linguistic change is a synchronic fact. (A. Sommerfelt)

b) Visible change is the tip of an iceberg. Every alteration that eventually establishes itself, had to exist formerly as a choice. This means that the seedbed for variation in time is simply the whole landscape of variation in space. (D. Bolinger)

c) The structure of language is nothing but the unstable balance between the needs of communication, which require more numerous and more specific units and man's inertia, which favours less numerous, less specific and more frequently occurring units. (A. Martinet)

d) That two forms, the new and the old, can occasionally exist in wholly free variation is a possibility that has not yet been disproved but, as Bloomfield rightly remarked "when a speaker knows two rival forms, they differ in connotation, since he has heard them from different persons under different circumstances". (M. Samuels)

Chapter II

GERMANIC LANGUAGES

Modern Germanic Languages (§ 32-33)

§ 32. Languages can be classified according to different principles. The historical, or genealogical classification, groups languages in accordance with their origin from a common linguistic ancestor.

Genetically, English belongs to the Germanic or Teutonic group of languages, which is one of the twelve groups of the IE linguistic family. Most of the area of Europe and large parts of other continents are occupied today by the IE languages, Germanic being one of their major groups.

§ 33. The Germanic languages in the modern world are as follows:

English — in Great Britain, Ireland, the USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the South African Republic, and many other former British colonies and dominions;

German — in the German Democratic Republic, the Federal Republic of Germany, Austria, Luxemburg, Liechtenstein, part of Switzerland;

Netherlandish — in the Netherlands and Flanders (Belgium) (known also as Dutch and Flemish respectively);

Afrikaans — in the South African Republic;

Danish — in Denmark;

Swedish — in Sweden and Finland;

Norwegian — in Norway;

Icelandic — inIceland;

Frisian — in some regions of the Netherlands and the Federal Republic of Germany;

Faroese — in the Faroe Islands;

Yiddish — in different countries.

Lists of Germanic languages given in manuals and reference-books differ in some points, for the distinction between separate languages, and also between languages and dialects varies. Until recently Dutch and Flemish were named as separate languages; Frisian and Faroese are often referred to as dialects, since they are spoken over small, politically dependent areas; the linguistic independence of Norwegian is questioned, for it has intermixed with Danish; Br E and Am E are sometimes regarded as two independent languages.

It is difficult to estimate the number of people speaking Germanic languages, especially on account of English, which in many countries is one of two languages in a bilingual community, e.g. in Canada. The estimates for English range from 250. to 300 million people who have it as their mother tongue. The total number of people speaking Germanic languages approaches 440 million. To this rough estimate we could add an indefinite number of bilingual people in the countries where English is used as an official language (over 50 countries).

All the Germanic languages are related through their common origin and joint development at the early stages of history. The survey of their external history will show where and when the Germanic languages arose and acquired their common features and also how they have developed into modern independent tongues.

The Earliest Period of Germanic History. Proto-Germanic (§ 34-35)

§ 34. The history of the Germanic group begins with the appearance of what is known as the Proto-Germanic (PG) language (also termed Common or Primitive Germanic, Primitive Teutonic and simply Germanic). PG is the linguistic ancestor or the parent-language of the Germanic group. It is supposed to have split from related IE tongues sometime between the 15th and 10th c. B.C. The would be Germanic tribes belonged to the western division of theIE speech community.

As the Indo-Europeans extended over a larger territory, the ancient Germans or Teutons[3] moved further north than other tribes and settled on the southern coast of the Baltic Sea in the region of the Elbe. This place is regarded as the most probable original home of the Teutons. It is here that they developed their first specifically Germanic linguistic features which made them a separate group in the IE family.

PG is an entirely pre-historical language: it was never recorded in written form. In the 19th c. it was reconstructed by methods of comparative linguistics from written evidence in descendant languages. Hypothetical reconstructed PG forms will sometimes be quoted below, to explain the origin of English forms.

It is believed that at the earliest stages of history PG was fundamentally one language, though dialectally coloured. In its later stages dialectal differences grew, so that towards the beginning of our era Germanic appears divided into dialectal groups and tribal dialects. Dialectal differentiation increased with the migrations and geographical expansion of the Teutons caused by overpopulation, poor agricultural technique and scanty natural resources in the areas of their original settlement.

The external history of the ancient Teutons around the beginning of our era is known from classical writings. The first mention of Germanic tribes was made by Pitheas, a Greek historian and geographer of the 4th c. B.C., in an account of a sea voyage to the Baltic Sea. In the 1st c. B.C. in COMMENTARIES ON THE GALLIC WAR (COM-MENTARII DE BELLO GALLICO) Julius Caesar described some militant Germanic tribes — the Suevians — who bordered on the Celts of Gaul in the North-East. The tribal names Germans and Teutons, at first applied to separate tribes, were later extended to the entire group. In the 1st c. A. D. Pliny the Elder, a prominent Roman scientist and writer, in NATURAL HISTORY (NATURALIS HISTORIA) made a classified list of Germanic tribes grouping them under six headings. A few decades later the Roman historian Tacitus compiled a detailed description of the life and customs of the ancient Teutons DE SITU, MORIBUS ET POPULIS GERMANIAE; in this work he reproduced Pliny's classification of the Germanic tribes, F. Engels made extensive use of these sources in the papers ON THE HISTORY OF THE ANCIENT GERMANS and THE ORIGIN OF THE FAMILY, PRIVATE PROPERTY AND THE STATE. Having made a linguistic analysis of several Germanic dialects of later ages F. Engels came to the conclusion that Pliny's classification of the Teutonic tribes accurately reflected the contemporary dialectal division. In his book on the ancient Teutons F. Engels described the evolution of the economic and social structure of the Teutons from Caesar's to Tacitus's time.

§ 35. Towards the beginning of our era the common period of Germanic history came to an end. The Teutons had extended over a larger territory and the PG language broke into parts. The tri-partite division of the Germanic languages proposed by 19th c. philologists corresponds, with a few adjustments, to Pliny's grouping of the Old Teutonic tribes. According to this division PG split into three branches: East Germanic (Vindili in Pliny's classification), North Germanic (Ffilteviones)and West Germanic (which embraces Ingveones, Istaevones and Herminones in Pliny's list). In due course these branches split into separate Germanic languages.

The traditional tri-partite classification of the Germanic languages was reconsidered and corrected in some recent publications. The development of the Germanic group was not confined to successive splits; it involved both linguistic divergence and convergence. It has also been discovered that originally PG split into two main branches and that the tri-partite division marks a later stage of its history.

The earliest migration of the Germanic tribes from the lower valley of the Elbe consisted in their movement north, to the Scandinavian peninsula, a few hundred years before our era. This geographical segregation must have led to linguistic differentiation and to the division of PG into the northern and southern branches. At the beginning of our era some of the tribes returned to the mainland and settled closer to the Vistula basin, east of the other continental Germanic tribes. It is only from this stage of their history that the Germanic languages can be described under three headings: East Germanic, North Germanic and West Germanic.

East Germanic (§ 36-37)

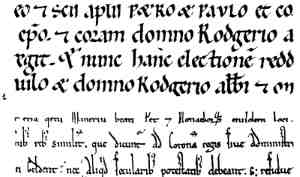

§ 36. The East Germanic subgroup was formed by the tribes who returned from Scandinavia at the beginning of our era. The most numerous and powerful of them were the Goths. They were among the first Teutons to leave the coast of the Baltic Sea and start on their great migrations. Around 200 A. D. they moved south-east and some time later reached the lower basin of the Danube, where they made attacks on the Eastern Roman Empire, Byzantium. Their western branch, the Visigotæ, invaded Roman territory, participated in the assaults on Rome under Alaric and moved on to southern Gaul, to found one of the first barbarian kingdoms of Medieval Europe, the Toulouse kingdom. The kingdom lasted until the 8th c. though linguistically the western Goths were soon absorbed by the native population, the Romanised Celts[4]. The eastern Goths, Ostrogotæconsolidated into a powerful tribal alliance in the lower basin of the Dniester, were subjugated by the Huns under Atilla, traversed the Balkans and set up a kingdom in Northern Italy, with Ravenna as its capital. The short-lived flourishing of Ostrogothic culture in the 5th—6th c. under Theodoric came to an end with the fall of the kingdom.

§ 37.The Gothic language, now dead, has been preserved in written records of the 4th-6th c. The Goths were the first of the Teutons to become Christian. In the 4th c. Ulfilas, a West Gothic bishop, made a translation of the Gospels from Greek into Gothic using a modified form of the Greek alphabet. Parts of Ulfilas' Gospels — a manuscript of about two hundred pages, probably made in the 5th or 6th c. — have been preserved and are kept now in Uppsala, Sweden. It is written on red parchment with silver and golden letters and is known as the SILVER CODEX (CODEX ARGENTEUS). Ulfilas' Gospels were first published in the 17th c. and have been thoroughly studied by 19th and 20th c. philologists. The SILVER CODEX is one of the earliest texts in the languages of the Germanic group; it represents a form of language very close to PG and therefore throws light on the pre-written stages of history of all the languages of the Germanic group, including English.

The other East Germanic languages, all of which are now dead, have left no written traces. Some of their tribal names have survived in place-names, which reveal the directions of their migrations; Bornholm and Burgundy go back to the East Germanic tribe of Burgundians; Andalusia is derived from the tribal name Vandals; Lombardy got its name from the Langobards, who made part of the population of the Ostrogothic kingdom in North Italy.

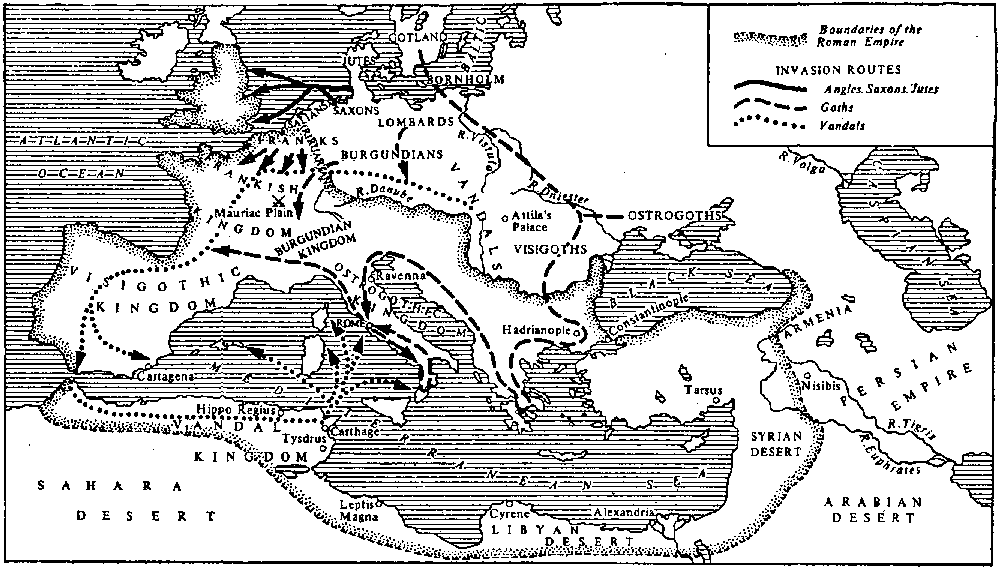

Migration of Germanic tribes in the 2nd-5th centuries

North Germanic (§ 38-41)

§ 38. The Teutons who stayed in Scandinavia after the departure of the Goths gave rise to the North Germanic subgroup of languages. The North Germanic tribes lived on the southern coast of the Scandinavian peninsula and in Northern Denmark (since the 4th c). They did not participate in the migrations and were relatively isolated, though they may have come into closer contacts with the western tribes after the Goths left the coast of the Baltic Sea. The speech of the North Germanic tribes showed little dialectal variation until the 9th c. and is regarded as a sort of common North Germanic parent-language called Old Norse or Old Scandinavian. It has come down to us in runic inscriptions dated from the 3rd to the 9th c. Runic inscriptions were carved on objects made of hard material in an original Germanic alphabet known as the runic alphabet or the runes. The runes were used by North and West Germanic tribes.

The disintegration of Old Norse into separate dialects and languages began after the 9th c. when the Scandinavians started out on their sea voyages. The famous Viking Age, from about 800 to 1050 A.D., is the legendary age of Scandinavian raids and expansion overseas. At the same period, due to overpopulation in the fjord areas, they spread over inner Scandinavia.

§39. The principal linguistic differentiation in Scandinavia corresponded to the political division into Sweden, Denmark and Norway. The three kingdoms constantly fought for dominance and the relative position of the three languages altered, as one or another of the powers prevailed over its neighbours. For several hundred years Denmark was the most powerful of the Scandinavian kingdoms: it embraced Southern Sweden, the greater part of the British Isles, the southern coast of the Baltic Sea up to the Gulf of Riga; by the 14th c. Norway fell under Danish rule too. Sweden regained its independence in the 16th c, while Norway remained a backward Danish colony up to the early 19th c. Consequently, both Swedish and Norwegian were influenced by Danish.

The earliest written records in Old Danish, Old Norwegian and Old Swedish date from the 13th c. In the later Middle Ages, with the growth of capitalist relations and the unification of the countries, Danish, and then Swedish developed into national literary languages. Nowadays Swedish is spoken not only by the population of Sweden; the language has extended over Finnish territory and is the second state language in Finland.

Norwegian was the last to develop into an independent national language. During the period of Danish dominance Norwegian intermixed with Danish. As a result in the 19th c. there emerged two varieties of the Norwegian tongue: the state or bookish tongue riksmal (later called bokmal)which is a blending of literary Danish with Norwegian town dialects and a rural variety, landsmal. Landsmal was sponsored by 19th c. writers and philologists as the real, pure Norwegian language. At the present time the two varieties tend to fuse info a single form of language nynorsk ("New Norwegian").

§ 40. In addition to the three languages on the mainland, the North Germanic subgroup includes two more languages: Icelandic and Faroese, whose origin goes back to the Viking Age.

Beginning with the 8th c. the Scandinavian sea-rovers and merchants undertook distant sea voyages and set up their colonies in many territories. The Scandinavian invaders, known as Northmen, overran Northern France and settled in Normandy (named after them). Crossing the Baltic Sea they came to Russia — the "varyagi" of the Russian chronicles. Crossing the North Sea they made disastrous attacks on English coastal towns and eventually occupied a large part of England — the Danes of the English chronicles. They founded numerous settlements in the islands around the North Sea: the Shetlands, the Orkneys, Ireland and the Faroe Islands; going still farther west they reached Iceland, Greenland and North America.

Linguistically, in most areas of their expansion, the Scandinavian settlers were assimilated by the native population: in France they adopted the French language; in Northern England, in Ireland and other islands around the British Isles sooner or later the Scandinavian dialects were displaced by English. In the Faroe Islands the West Norwegian dialects brought by the Scandinavians developed into a separate language called Faroese. Faroese is spoken nowadays by about 30,000 people. For many centuries all writing was done in Danish; it was not until the 18th c. that the first Faroese records were made.

§ 41. Iceland was practically uninhabited at the time of the first Scandinavian settlements (9th c). Their West Scandinavian dialects, at first identical with those of Norway, eventually grew into an independent language, Icelandic. It developed as a separate language in spite of the political dependence of Iceland upon Denmark and the dominance of Danish in official spheres. As compared with other North Germanic languages Icelandic has retained a more archaic vocabulary and grammatical system. Modern Icelandic is very much like Old Icelandic and Old Norse, for it has not participated in the linguistic changes which took place in the other Scandinavian languages, probably because of its geographical isolation. At present Icelandic is spoken by over 200 000 people.

Old Icelandic written records date from the 12th and 13th c., an age of literary flourishing. The most important records are: the ELDER EDDA (also called the POETIC EDDA) — a collection of heroic songs of the 12th c, the YOUNGER (PROSE) EDDA (a text-book for poets compiled by Snorri Sturluson in the early 13th c.) and the Old Icelandic sagas.

West Germanic (§ 42-48)

§ 42. Around the beginning of our era the would-be West Germanic tribes dwelt in the lowlands between the Oder and the Elbe bordering on the Slavonian tribes in the East and the Celtic tribes in the South. They must have retreated further west under the pressure of the Goths, who had come from Scandinavia, but after their departure expanded in the eastern and southern directions. The dialectal differentiation of West Germanic was probably quite distinct even at the beginning of our era since Pliny and Tacitus described them under three tribal names (see § 35). On the eve of their "great migrations" of the 4th and 5th c. the West Germans included several tribes. The Franconians (or Franks) occupied the lower basin of the Rhine; from there they spread up the Rhine and are accordingly subdivided into Low, Middle and High Franconians. The Angles and the Frisians (known as the Anglo-Frisian group), the Jutes and the Saxons inhabited the coastal area of the modern Netherlands, the Federal Republic of Germany and the southern part of Denmark. A group of tribes known as High Germans lived in the mountainous southern regions of the Federal Republic of Germany thence the name High Germans as contrasted to Low Germans — a name applied to the West Germanic tribes in the low-lying northern areas. The High Germans included a number of tribes whose names are known since the early Middle Ages: the Alemanians, the Swabians, the Bavarians, the Thuringians and others.

In the Early Middle Ages the Franks consolidated into a powerful tribal alliance. Towards the 8th c. their kingdom grew into one of the largest states in Western Europe. Under Charlemagne (768-814) the Holy Roman Empire of the Franks embraced France and half of Italy, and. stretched northwards up to the North and Baltic Sea. The empire lacked ethnic and economic unity and in the 9th c. broke up into parts. Its western part eventually became the basis of France. Though the names France, French are derived from the tribal name of the Franks, the Franconian dialects were not spoken there. The population, the Romanised Celts of Gaul, spoke a local variety of Latin, which developed into one of the most extensive Romance languages, French.

The eastern part, the East Franconian Empire, comprised several kingdoms: Swabia or Alemania, Bavaria, East Franconia and Saxony; to these were soon added two more kingdoms — Lorraine and Friesland. As seen from the names of the kingdoms, the East Franconian state had a mixed population consisting of several West Germanic tribes.

§ 43. The Franconian dialects were spoken in the extreme North of the Empire; in the later Middle Ages they developed into Dutch — the language of the Low Countries (the Netherlands) and Flemish — the language of Flanders. The earliest texts in Low Franconian date from the 10th c; 12th c. records represent the earliest Old Dutch. The formation of the Dutch language stretches over a long period; it is linked up with the growth of the Netherlands into an independent bourgeois state after its liberation from Spain in the I6th c.

The modern language of the Netherlands, formerly called Dutch, and its variant in Belgium, known as the Flemish dialect, are now treated as a single language, Netherlandish. Netherlandish is spoken by almost 20 million people; its northern variety, used in the Netherlands, has a more standardised literary form-About three hundred years ago the Dutch language was brought to South Africa by colonists from Southern Holland. Their dialects in Africa eventually grew into a separate West Germanic language, Afrikaans. Afrikaans has incorporated elements from the speech of English and German colonists in Africa and from the tongues of the natives. Writing in Afrikaans began as late as the end of the 19th c. Today Afrikaans is the mother-tongue of over four million Afrikaners and coloured people and one of the state languages in the South African Republic (alongside English).

§ 44. The High German group of tribes did not go far in their migrations. Together with the Saxons (see below § 46 ff.) the Alemanians, Bavarians, and Thuringians expanded east, driving the Slavonic tribes from places of their early settlement.

The High German dialects consolidated into a common language known as Old High German (OHG). The first written records in OHG date from the 8th and 9th c. (glosses to Latin texts, translations from Latin and religious poems). Towards the 12th c. High German (known as Middle High German) had intermixed with neighbouring tongues, especially Middle and High Franconian, and eventually developed into the literary German language. The Written Standard of New High German was established after the Reformation (16th c), though no Spoken Standard existed until the 19th c. as Germany remained politically divided into a number of kingdoms and dukedoms. To this day German is remarkable for great dialectal diversity of speech.

The High German language in a somewhat modified form is the national language of Austria, the language of Liechtenstein and one of the languages in Luxemburg and Switzerland. It is also spoken in Alsace and Lorraine in France. The total number of German-speaking people approaches 100 million.

§ 45.Another offshoot of High German is Yiddish. It grew from the High German dialects which were adopted by numerous Jewish communities scattered over Germany in the 11th and 12th c. These dialects blended with elements of Hebrew and Slavonic and developed into a separate West Germanic language with a spoken and literary form. Yiddish was exported from Germany to many other countries: Russia, Poland, the Baltic states and America.

§ 46. At the later stage of the great migration period — in the 5th c. — a group of West Germanic tribes started out on their invasion of the British Isles. The invaders came from the lowlands near the North Sea: the Angles, part of the Saxons and Frisians, and, probably, the Jutes. Their dialects in the British Isles developed into the English language.

The territory of English was at first confined to what is now known as England proper. From the 13th to the 17th c. it extended to other parts of the British Isles. In the succeeding centuries English spread overseas to other continents. The first English written records have come down from the 7th c, which is the earliest date in the history of writing in the West Germanic subgroup (see relevant chapters below).

§ 47. The Frisians and the Saxons who did not take part in the invasion of Britain stayed on the continent. The area of Frisians, which at one time extended over the entire coast of the North Sea, was reduced under the pressure of other Low German tribes and the influence of their dialects, particularly Low Franconian (later Dutch). Frisian has survived as a local dialect in Friesland (in the Netherlands) and Ostfriesland (the Federal Republic of Germany). It has both an oral and written form, the earliest records dating from the 13th c.

§ 48. In the Early Middle Ages the continental Saxons formed a powerful tribe in the lower basin of the Elbe. They were subjugated by the Franks and after the breakup of the Empire entered its eastern subdivision. Together with High German tribes they took part in the eastward drive and the colonisation of the former Slavonic territories. Old Saxon known in written form from the records of the 9th c. has survived as one of the Low German dialects.

§ 49. The following table shows the classification of old and modern Germanic languages.

Table

Germanic Languages (§ 49)

| East Germanic | North Germanic | West Germanic | |

| Old Germanic languages (with dates of the earliest records) | Gothic (4th c.) Vandalic Burgundian | Old Norse or Old Scandinavian (2nd-3rd c.) Old Icelandic (12th c.) Old Norwegian (13th c.) Old Danish (13th c.) Old Swedish (13th c.) | Anglian, Frisian, Jutish, Saxon, Franconian, High German (Alemanic, Thuringian, Swavian, Bavarian) Old English (7th c.) Old Saxon (9th c.) Old High German (8th. c.) Old Dutch (12th c.) |

| Modern Germanic languages | No living languages | Icelandic Norwegian Danish Swedish Faroese | English German Netherlandish Afrikaans Yiddish Frisian |

Chapter III

LINGUISTIC FEATURES OF GERMANIC LANGUAGES

Preliminary Remarks (§ 50)

§ 50.All the Germanic languages of the past and present have common linguistic features; some of these features are shared by other groups in the IE family, others are specifically Germanic.

The Germanic group acquired their specific distinctive features after the separation of the ancient Germanic tribes from other IE tribes and prior to their further expansion and disintegration, that is during the period of the PG parent-language. These PG features inherited by the descendant languages, represent the common features of the Germanic group. Other common features developed later, in the course of the individual histories of separate Germanic languages, as a result of similar tendencies arising from PG causes. On the other hand, many Germanic features have been disguised, transformed and even lost in later history.

PHONETICS (§ 51-61)

Word Stress (§ 51-52)

§ 51. The peculiar Germanic system of word accentuation is one of the most important distinguishing features of the group; it arose in PG, was fully or partly retained in separate languages and served as one of the major causes for many linguistic changes.

It is known that in ancient IE, prior to the separation of Germanic, there existed two ways of word accentuation: musical pitch and force stress. The position of the stress was free and movable, which means that it could fall on any syllable of the word — a root-morpheme, an affix or an ending — and could be shifted both in form-building and word-building (cf. R дóмом, домá, домовничать, дóма).

Both these properties of the word accent were changed in PG. Force or expiratory stress (also called dynamic and breath stress) became the only type of stress used. In Early PG word stress was still as movable as in ancient IE but in Late PG its position in the word was stabilised. The stress was now fixed on the first syllable, which was usually the root of the word and sometimes the prefix; the other syllables — suffixes and endings — were unstressed. The stress could no longer move either in form-building or word-building.

These features of word accent were inherited by the Germanic languages, and despite later alterations are observable today. In Mod E there is a sharp contrast between accented and unaccented syllables due to the force of the stress. The main accent commonly falls on the root-morpheme, and is never shifted in building grammatical forms. The following English and German words illustrate its fixed position in grammatical forms and derived words:

English: be'come, be'coming, over'come; 'lover, 'loving, be'loved;

German: 'Liebe, 'lieben 'lieble, ge'liebt, 'lieberhaft, 'Liebling.

(Cf. these native words with words of foreign origin which move the stress in derivation, though never in form-building: ex'hibit v, exhibition n).

§ 52. The heavy fixed word stress inherited from PG has played an important role in the development of the Germanic languages, and especially in phonetic and morphological changes. Due to the difference in the force of articulation the stressed and unstressed syllables underwent widely different changes: accented syllables were pronounced with great distinctness and precision, while unaccented became less distinct and were phonetically weakened. The differences between the sounds in stressed position were preserved and emphasised, whereas the contrasts between the unaccented sounds were weakened and lost. Since the stress was fixed on the root, the weakening and loss of sounds mainly affected the suffixes and grammatical endings. Many endings merged with the suffixes, were weakened and dropped. Cf., e.g., the reconstructed PG word ‘fish’, with its descendants in Old Germanic languages:

PG *fiskaz, Gt fisks, O Icel fiskr, OE fisc.

(The asterisk * is placed before reconstructed hypothetical forms which have not been found in written records; the words may be pronounced exactly as they are written; spelling in Old Germanic languages was phonetic).

Vowels (§ 53-56)

§ 53.Throughout history, beginning with PG, vowels displayed a strong tendency to change. They underwent different kinds of alterations: qualitative and quantitative, dependent and independent. Qualitative changes affect the quality of the sound, e.g.: [o > a ] or [p > f]; quantitative changes make long sounds short or short sounds long, e.g.: [i > i:], [ll > l]; dependent changes (also positional or combinative)are restricted to certain positions or phonetic conditions, for instance, a sound may change under the influence of the neighbouring sounds or in a certain type of a syllable; independent changes — also spontaneous or regular — take place irrespective of phonetic conditions, i.e. they affect a certain sound in all positions.

From an early date the treatment of vowels was determined by the nature of word stress. In accented syllables the oppositions between vowels were carefully maintained and new distinctive features were introduced, so that the number of stressed vowels grew. In unaccented positions the original contrasts between vowels were weakened or lost; the distinction of short and long vowels was neutralised so that by the age of writing the long vowels in unstressed syllables had been shortened. As for originally short vowels, they tended to be reduced to a neutral sound, losing their qualitative distinctions and were often dropped in unstressed final syllables (see the example *fiskaz in § 52).

§ 54. Strict differentiation of long and short vowels is commonly regarded as an important characteristic of the Germanic group. The contrast of short and long vowels is supported by the different directions of their changes. While long vowels generally tended to become closer and to diphthongise, short vowels, on the contrary, often changed into more open sounds. These tendencies can be seen in the earliest vowel changes which distinguished the PG vowel system from its PIE source.

IE short [o] changed in Germanic into the more open vowel [a] and thus ceased to be distinguished from the original IE [a];in other words inPG they merged into [o]. The merging of long vowels proceeded inthe opposite direction: IE long [a:] was narrowed to [o:] and merged with [o:]. The examples in Table 1 illustrate the resulting correspondences of vowels in parallels from Germanic and non-Germanic languages (more apparent in Old Germanic languages than inmodern words, for the sounds have been modified in later history).

Table 1

Independent Vowel Changes in Proto-Germanic

| Change illustrated | Examples | |||

| PIE | PG | Non-Germanic | Germanic | |

| Old | Modern | |||

| o | a | L nox, Ir nochd, R ночь R могу; мочь | Gt nahts, О Icel natt, OHG naht Gt magan, OE maʒan, mæʒ | Sw natt, G Nacht Sw ma, NE may |

| a: | o: | L mater, R мать O Ind bhrata, L frater, R брат | O Icel moðir, OE modor Gt bropar, O Icel broðir, OE broðor | Sw moder, NE mother Sw broder, NE brother |

§ 55. In later PG and in separate Germanic languages the vowels displayed a tendency to positional assimilative changes: the pronunciation of a vowel was modified under the influence of the following or preceding consonant; sometimes a vowel was approximated more closely to the following vowel. The resulting sounds were phonetically conditioned allophones which could eventually coincide with another phoneme or develop into a new phoneme.

The earliest instances of progressive assimilation were common Germanic mutations; they occurred in Late PG before its disintegration or a short time after. In certain phonetic conditions, namely before the nasal [n] and before [i] or [j] in the next syllable the short [e], [j] and [u] remained orbecame close (i.e. appeared as [i] and [u]), while in the absence of these conditions the more open allophones were used; [e] and [o], respectively. Later, these phonetic conditions became irrelevant and the allophones were phonologised.

Table 2

Mutation of Vowels in Late PG

| Change illustrated | Examples | ||

| Non-Germanic | Germanic | ||

| Old | Modern | ||

| PIE G | L ventus, R ветер | Gt winds, O Icel vindr, OE wind | Sw vind, NE wind |

| i e e | L edit, R ест L edere, R есть | OHG izit, OE itep, O Icel eta, OE etan | G iβt, NE eats, G essen, NE eat |

| u u o | Lith sunus, R сын Celt human | O Icel sunr, OE sunu O Icel, OE horn | Sw son, NE son NE horn, Sw horn |

§ 56. After the changes, in Late PG, the vowel system contained the following sounds:

SHORT VOWELS i e a o u

LONG VOWELS i: e: a: o: u:[5]

It is believed that in addition to these monophthongs PG had a set of diphthongs made up of more open nuclei and closer glides: [ei], [ai]. [eu], [au] and also [iu]; nowadays, however, many scholars interpret them as sequences of two independent monophthongs.

Consonants. Proto-germanic consonant shift (§ 57-59)

§ 57. The specific peculiarities of consonants constitute the most remarkable distinctive feature of the Germanic linguistic group. Comparison with other languages within the IE family reveals regular correspondences between Germanic and non-Germanic consonants. Thus we regularly find [f] in Germanic where other IE languages have [p]; cf. e.g., E full,R полный,Fr plein;wherever Germanic has [p], cognate words in non-Germanic languages have [b] (cf. E pool, R болото).The consonants in Germanic look ‘shifted’ as compared with the consonants of non-Germanic languages. The alterations of the consonants took place in PG, and the resulting sounds were inherited by the languages of the Germanic group.

The changes of consonants in PG were first formulated in terms of a phonetic law by Jacob Grimm in the early 19th c. and are often called Grimm's Law. It is also known as the First or Proto-Germanic consonant shift (to be distinguished from the 2nd shift which took place in OHG in the 9th c.).

By the terms of Grimm's Law voiceless plosives developed in PG into voiceless fricatives (Act I); IE voiced plosives were shifted to voiceless plosives (Act II) and IE voiced aspirated plosives were reflected (See Note 1 to Table 3) either as voiced fricatives or as pure voiced plosives (Act III).

Table 3

Consonant. Shift in Proto-Germanic (Grimm's Law)

| Correspondence illustrated | Examples | ||||||

| Non-Germanic | Germanic | ||||||

| Old | Modern | ||||||

| PIE | PG | ||||||

| ACT I | |||||||

| p | f | L pes, pedis | Gt fotus, O Icel fotr, OE fot | Sw fot, NE foot G Fuβ | |||

| R пена | OE fam | G Feim, NE foam | |||||

| L piscis, R пескарь | Gt fisks, OE fisc | G Fisch, NE fish | |||||

| t | θ | L tres, R три | Gt preis, O Icel prir, OE preo | Sw tre, G drei, NE three | |||

| L tu, Fr tu, R ты | Gt pu, OE pu | G Sw du, NE thou | |||||

| k | x | L cor, cordis, Fr coeur, R сердце | Gt hairto, O Icel hjarta, OE heort | G Herz, NE heart | |||

| L canis R колода | Gt hunds, OE hund OE holt | G Hund, NE hound G Holz, NE holt | |||||

| ACT II | |||||||

| b | p | Lith bala, R болото | OHG pfuol, OE pol | G Pfuhl, NE pool | |||

| L labare, R слабый | Gt slepan, OE slæpan | G schlafen, NE steep | |||||

| d | t | L decem, Fr dix, R десять | Gt taihun, O Icel tiu, OE tien | Sw tio, G zehn, NE ten | |||

| Fr deux, R два | OF twa | NE two | |||||

| L edere, R еда | Gt itan, OE etan | Sw ata, NE ear | |||||

| L. videre, R ведать, видеть | OF witan | G wissen, NE wit | |||||

| g | k | L genu, Fr genou L ager | OE cneo, Gt kniu Gt akrs, O Icel akr, OE æcer | NE knee, G Knie Sw aker, NE acre | |||

| L iugum, R иго | Gt juk, O Icel ok, OE ʒeoc | Sw ok, NE yoke | |||||

| ACT III | |||||||

| bh[6] | v (or b) | O Ind bhrata, L frater, R брат | Gt bropar, O Icel bróðir, OE bropor | Sw broder, G Bruder, NE brother | |||

| L ferre, R беру | Gt bairan, OE beran | G gebären, NE bear | |||||

| Fr future, R быть | OHG bin, bist, OE bēon | G bin, bist, NE be | |||||

| dh | ð (or d) | O Ind rudhira, R рдеть | Gt raups, O Icel rauðr, OE rēad | G rot, Sw röd, NE red | |||

| O Ind mádhyas, L medius | Gt midjis [ð], OE middel | G Mittel, NE middle | |||||

| R делать | Gt gadeps, OE dæd, dōn | NE deed, do | |||||

| gh | γ (or g) | L hostis, R гость | Gt gasts, O Icel gestr, OE giest | Sw gäst, G Gast, NE guest | |||

| L (leg-) lectus, R залегать | Gt ligan [γ], O Icel liggja, OE licʒan | G liegen, NE lie | |||||

| O Ind vaha, L via, R везти | Gt wiga [γ], O Icel vegr, OE weʒ | Sw väg, G Weg, NE way | |||||

§ 58. Another important series of consonant changes in PG was discovered in the late 19th c. by a Danish scholar, Carl Verner. They are known as Verner's Law. Vemer's Law explains some correspondences of consonants which seemed to contradict Grimm's Law and were for a long time regarded as exceptions. According to Verner's Law all the early PG voiceless fricatives [f, θ, x] which arose under Grimm's Law, and also is) inherited from PIE, became voiced between vowels if the preceding vowel was unstressed; in the absence of these conditions they remained voiceless. The voicing occurred in early PG at the time when the stress was not yet fixed on the root-morpheme. The process of voicing can be shown as a step in a succession of consonant changes in prehistorical reconstructed forms; consider, e.g. the changes of the second consonant in the word father:

| PIE | Early PG | Late PG |

| *pa'ter | > *fa'θar > *fa'ðar > | >*'faðar |

Verner's Law accounts for the appearance of voiced fricative or its later modifications [d] in place of the voiceless [θ] which ought to be expected under Grimm's Law. In late PG, the phonetic conditions that caused the voicing had disappeared: the stress had shifted to the first syllable.

Table 4

Voicing of Fricatives in Proto-Germanic (Verner's Law)

| Change illustrated | Examples | |||

| PIE | PG | Non-Germanic | Germanic | |

| Early Late | old | modern | ||

| p | f > v | L caput | Gt haubip, O Icel haufoð, OE hēafod [v] | Sw huvud, G Haupt , NE head |

| L septem | Gt sibun, OE seofon [v] | G sieben, NE seven | ||

| t | θ >ð,d | O Ind satam, R сто | Gt hund, O Icel hundrað, OE hund | G Hundert, Sw hundrade, NE hundred |

| L pater, O Ind pita | Gt fadar [ð], O Icel faðir, OE fæder | G Vater, Sw fader, NE father | ||

| k | x > γ,g | L cunctāari | O Icel hanga, OE hanʒian | Sw hänga, NE hang |

| L socrus, R свекровь | Gt swaihro, OHG swigur, OE sweser | G Schwager | ||

| s | s > z | L auris, Lith ausis | Gt auso, O Icel eyra, OE ēare | Swöra, G Ohr, NE ear |

| (Note: [z] in many languages became [r]) |

§ 59. As a result at voicing by Verner's Law there arose an interchange of consonants in the grammatical forms of the word, termed grammatical interchange. Part of the forms retained a voiceless fricative, while other forms — with a different position of stress in Early PG — acquired a voiced fricative. Both consonants could undergo later changes in the OG languages, but the original difference between them goes back to the time of movable word stress and PG voicing. The interchanges can be seen in the principal forms of some OG verbs, though even at that time most of the interchanges were levelled out by analogy.

Table 5

Grammatical Interchanges of Consonants caused by Verner's Law

| Interchange | Principal forms of the verbs | |||||

| PG | OG languages | Infinitive | Past Tense | Participle II | NE | |

| sg | pl | |||||

| f ~ v | OHG f ~ b | heffen | huob | huobun | gi-haban | heave |

| ð~ θ | OE ð/θ ~ d | sēoðan | sēað | sudon | soden | seethe |

| x ~ y | O Icel, | slá | sló | slógum | sleginn | |

| OE x ~ y | slēan | slōʒon | slæʒen | slay | ||

| s ~ z | OE s/z ~ r | cēosan | cēas | curon | coren | choose |

Note that some Mod E words have retained traces of Verner's Law, e. g. seethe — sodden; death — dead; raise — rear; was — were.

Interpretation of the Proto-Germanic Consonant Shift (§ 60-61)

§ 60. The causes and mechanism of the PG consonant shift have been a matter of discussion ever since the shift was discovered.

When Jacob Grimm first formulated the law of the shift he ascribed it to the allegedly daring spirit of the Germanic tribes which manifested itself both in their great migrations and in radical linguistic innovations. His theory has long been rejected as naive and romantic.

Some philologists attributed the shift to the physiological peculiarities of the Teutons, namely the shape of their glottis: it differed from that of other IB tribes, and the pronunciation of consonants was modified. Other scholars maintained that the consonant shift was caused by a more energetic articulation of sounds brought about by the specifically Germanic force word stress. Another theory suggested that the articulation of consonants in Germanic was, on the contrary, marked by lack of energy and tension.

The theory of "linguistic substratum" which was popular with many 20th c. linguists, attributes the PG consonant changes — as well as other Germanic innovations — to the influence of the speech habits of pre-Germanic population in the areas of Germanic settlement. The language of those unknown tribes served as a sort ol substratum (‘under-layer’) for the would-be Germanic tongues; it intermixed with the language of the Teutons and left certain traces in PG. This hypothesis can be neither confirmed nor disproved, since we possess no intamation about the language of pre-IE inhabitants of Western Europe.

According to recent theories the PG consonant shift could be caused by the internal requirements of the language system: the need for more precise phonemic distinction reliable in all phonetic conditions. Before the shift (according to J. Kurylowicz) the opposition of voiced and voiceless plosives was neutralised (that is, lost) in some positions, namely before the sound [s]; therefore new distinctive features arose in place of or in addition to sonority. [p, t, k] changed into [f, 0, x] and began to be contrasted to [b, d, g] not only through sonority but also through the manner of articulation as fricatives to plosives. This change led to further changes: since [f, 0, x]were now opposed to [b, d, g] through their fricative character, sonority became irrelevant for phonemic distinction and [b, d, g]were devoiced: they changed into [p, t, k], respectively. That is how the initial step stimulated further changes and the entire system was shifted. It is essential that throughout the shift the original pattern of the consonant system was preserved; three rows of noise consonants were distinguished, though instead of opposition through sonority consonants were opposed as fricatives to plosives. (For a critical review of various theories see «Сравнительная грамматика германских языков", M., 1962, кн. II, ч. I, гл. 1, 7.1 — 6.5.)

Another explanation based on the structural approach to language interprets the role of the language system from a different angle. Every subsystem in language tends to preserve a balanced, symmetrical arrangement: if the balance is broken, it will soon be restored by means of new changes. After the replacement of [p, t, k] by [f, 0, k] the positions of the voiceless [p, t, k] in the consonant system were left vacant; to fill the vacuums and restore the equilibrium [b, d, g]were devoiced into [p, t, k]. In their turn the vacant positions of [b, d, g] were filled again in the succeeding set of changes, when [bh, dh, gh] lost their aspirated character. This theory, showing the shift as a chain of successive steps, fails to account for the initial push.

§ 61. The chronology of the shift and the relative order of the changes included in Grimm's Law and Verner's Law, has also aroused much interest and speculation. It is believed that the consonant shift was realised as a series of successive steps; it began first on part of Germanic territories and gradually spread over the whole area. The change of [p, t, k] into fricatives is unanimously regarded as the earliest step — the first act of Grimm's Law; it was followed, or, perhaps, accompanied by the voicing of fricatives (Verner's Law), Linguists of the 19th c. were inclined to refer the voicing of fricatives to a far later date than the first act of Grimm's Law, However, there are no grounds to think that the effect of word stress and intervocal position on sonority could have been much delayed. In all probability, the IE plosives split into voiced and voiceless sounds soon after they had acquired their fricative character or even during that process.

The order of the other two steps (or acts of Grimm's Law) varies in different descriptions of the shift.

GRAMMAR (§ 62-69)

Form-building Means (§ 62)

§ 62. Like other old IE languages both PG and the OG languages had a synthetic grammatical structure, which means that the relationships between the parts of the sentence were shown by the forms of the words rather than by their position or by auxiliary words. In later history all the Germanic languages developed analytical forms and ways of word connection.

In the early periods of history the grammatical forms were built in the synthetic way: by means of inflections, sound interchanges and suppletion.

The suppletive way of form-building was inherited from ancient IE, it was restricted to a few personal pronouns, adjectives and verbs.

Compare the following forms of pronouns in Germanic and non-Germanic languages:

| L | Fr | R | Gt | O Icel | OE | NE |

| ego | je | я | ik | ek | ic | I |

| mei | mon | меня | meina | min | min | my, mine |

| mihi | me, moi | мне | mis | mer | me | me |

The principal means of form-building were inflections. The inflections found in OG written records correspond to the inflections used in non-Germanic languages, having descended from the same original IE prototypes. Most of them, however, were simpler and shorter, as they had been shortened and weakened in PG.

The wide use of sound interchanges has always been a characteristic feature of the Germanic group. This form-building (and word-building) device was inherited from IE and became very productive in Germanic. In various forms of the word and in words derived from one and the same root, the root-morpheme appeared as a set of variants. The consonants were relatively stable, the vowels were variable[7]. Table 6 shows the variability of the root *ber- in different grammatical forms and words.

Table 6

Variants of the Root *ber-

| Old Germanic languages | Modern Germanic languages | |||||

| Gt | O Icel | OE | Sw | G | NE | |

| forms of the verb bear | bairan | bera | beran | bära | gebären | bear |

| bar | bar | bær | bar | gebar | bore (sg) | |

| berum | bárum | bæron | buro | — | (Pi) | |

| baurans | borinn | boren | buren | geboren | born | |

| birp | bears | |||||

| other words from the -ame root | barn | barn | bearn | barn | Geburt | barn (dial, ‘child’) |

| baur | burðr | ʒebyrd | birth | |||

| byrð |

Vowel Gradation with Special Reference to Verbs (§ 63-65)

§ 63. Vowel interchanges found in Old and Modern Germanic languages originated at different historical periods. The earliest set of vowel interchanges, which dates from PG and PIE, is called vowel gradation or ablaut. Ablaut is an independent vowel interchange unconnected with any phonetic conditions; different vowels appear in the same environment, surrounded by the same sounds (all the words in Table 6 are examples of ablaut with the exception of the forms containing [i] and [y] which arose from positional changes.

Vowel gradation did not reflect any phonetic changes but was used as a special independent device to differentiate between words and grammatical forms built from the same root.

Ablaut was inherited by Germanic from ancient IE. The principal gradation series used in the IE languages — [e ~ o] — can be shown in Russian examples: нести ~ ноша.This kind of ablaut is called qualitative, as the vowels differ only in quality. Alternation of short and long vowels, and also alternation with a "zero" (i.e. lack of vowel) represent quantitative ablaut:

| Prolonged grade (long vowel) | Normal or lull grade (short vowel) | Reduced grade (zero grade) (neutral vowel or loss of vowel) |

| ē | e | |

| L lēgi ‘elected’ | lego ‘elect’ | |

| R — | e ~ o | |

| беру — сбор | брал |

The Germanic languages employed both types of ablaut — qualitative and quantitative, — and their combinations. In accordance with vowel changes which distinguished Germanic from non-Germanic the gradation series were modified: IE [e ~ o] was changed to [e/i ~ a]; likewise, quantitative ablaut [a ~a:] was reflected in Germanic as a quantitative-qualitative series [a ~ o:] (for relevant vowel changes see § 53,54). Quantitative ablaut gave rise to a variety of gradation series in Germanic owing to different treatment of the zero-grade in various phonetic conditions.

§ 64. Of all its spheres of application in Germanic ablaut was most consistently used in building the principal forms of the verbs called strong. Each form was characterised by a certain grade; each set of principal forms of the verb employed a gradation series. Gradation vowels were combined with other sounds in different classes of verbs and thus yielded several new gradation series. The use of ablaut in the principal forms of ‘bear’ was shown in Table 6. The Gothic verbs in Table 6 give the closest possible approximation to PG gradation series, which were inherited by all the OG languages and were modified in accordance with later phonetic changes (see OE strong verbs § 200-203)

Table 7

Examples of Vowel Gradation in Gothic Strong Verbs

| IE | e | zero | zero | |

| PG | e/i | a | zero | zero |

| Principal forms |

Дата добавления: 2016-05-31; просмотров: 5984;