HOW TUNNELS ARE BUILT

People dig some tunnels through rock or soft earth. Other tunnels, known as submerged tunnels, lie in trenches dug into the bottoms of rivers or other bodies of water.

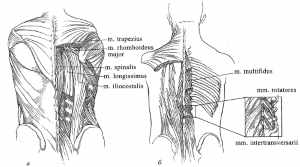

Rock tunnels.The construction of most rock tunnels involves blasting. To blast rock, workers first move a scaffold called a jumbo next to the tunnel face (front). Mounted on the jumbo are several drills, which bore holes into the rock. The holes are usually about 10 feet (3 meters) long, but may be longer or shorter depending on the rock. The holes measure only a few inches or centimeters in diameter. Workers pack explosives into the holes. After these charges are exploded and the fumes sucked out, carts carry away the pieces of rock, called muck.

If the tunnel is strong, solid rock, it may not require extra support for its roof and walls. But most rock tunnels are built through rock that is naturally broken into large blocks or contains pockets of fractured rock. To prevent this fragmented rock from falling, workers usually insert long bolts through the rock or spray it with concrete. Sometimes they apply a steel mesh first to help hold broken rock. Workers using an older method erect rings of steel beams or timbers. In most cases, they add a permanent lining of concrete later.

Tunnel-boring machines dig tunnels in soft, but firm rock such as limestone or shale and in hard rock such as granite. A circular plate covered with disk cutters is attached to the front of these machines. As the plate rotates slowly, the disk cutters slice into the rock. Scoops on the machine carry the muck to a conveyor that removes it to the rear. To cut weaker rock such as sandstone, workers use road header's and other machinery.

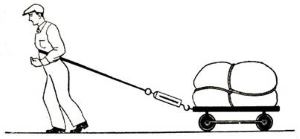

Earth tunnelsinclude tunnels that are dug through clay, silt, sand, or gravel, or in muddy riverbeds. Tunneling through such soft earth is especially dangerous because of the threat of cave-ins. In most cases, the roof and walls of a section of tunnel dug through these materials are held up by a steel cylinder called a shield.Workers leave the shield in place while they remove the earth inside it and install a permanent lining of cast iron or precast concrete. After this work is completed, jacks push the shield into the earth ahead of the tunnel, and the process is repeated. Some tunnel-boring machines have a shield attached to them and are able to position sections of concrete tunnel lining into place as they dig. Such a machine dug part of the London subway system

If the soil is strong enough to stand by itself for at least a few hours, workers may not use concrete sections. Instead, they would hold the soil in place with bolts, steel ribs, and sprayed concrete.

Tunneling through the earth beneath bodies of water adds the danger of flooding to that of cave-ins. Engineers generally prevent water from entering a tunnel during construction by compressing the air in the end of the tunnel where the work is going on. When the air pressure inside the tunnel exceeds the pressure of the water outside, the water is kept out. This method was used to build the subway tunnels under the East River in New York City and the River Thames in London.

Submerged tunnelsare built across the bottoms of rivers, bays, and other bodies of water. Submerged tunnels are generally less expensive to build than those dug by the shield or compressed-air methods. Construction begins by dredging a trench for the tunnel. Closed-ended steel or concrete tunnel sections are then floated over the trench and sunk into place. Next, divers connect the sections and remove the ends, and any water in the tunnel is pumped out. In most cases, the tunnels are then covered with earth. Submerged tunnels include the railroad tunnel under the Detroit River and the rapid transit tunnel under San Francisco Bay.

How а tunnel is constructed

How а tunnel is constructed

А tunnel-boring machine digs into rock with attachments called disk cutters. The broken rock, called muck then is removed bу conveyor and rail саг and brought to the surface in аn elevator. Meanwhile, concrete sections of the tunnel lining аге lowered through а shaft. А shield оп the tunnel-boring machine holds uр the roof until workers can erect а new section of tunnel lining.

The Mersey Tunnel

3. What are the purposes of underwater tunnels?

3. What are the purposes of underwater tunnels?

The cities of Liverpool and Birkenhead are joined by a tunnel which goes under the river Mersey. It is the famous Mersey Tunnel, one of the biggest underwater tunnels in the world. Its total length is over two and a half miles. During the year 1956 more than 10 million vehicles used the tunnel. Its construction has been a great engineering achievement. The work started in December 1925 on the Liverpool side and a few months later on the Birkenhead side. It had been decided to approach the work by driving from each bank of the river two pilot headings, an upper and a lower one, which would meet under the middle part of the river. Vertical shafts were sunk on both sides of the river and the excavation work began. At first the working face of the heading was broken up by compressed air drills, later explosives were used. The headings met on the 3rd of April, 1928, twenty-seven months after the work had begun. The divergences in line and level were found to be a fraction of an inch, showing how accurately and correctly the survey work and the determination of working levels had been done. The next stage of the work was the enlarging of the pilot headings into the full-sized tunnel. Steel, cast iron and concrete were used in lining the tunnel. From the very start it was realised that the ventilation of a tunnel of such length, which was to be used by vehicles propelled by internal combustion, would be a very difficult problem. Finally, a system of ventilation was adopted in which air is blown into the tunnel through ducts at roadway level and drawn off along the roof through exhausts. The Mersey Tunnel was completed in 1934. It was opened on the 18th of July, 1934. At the time it seemed a complete solution of the communication difficulties that had existed between Liverpool and Birkenhead. Today it is obvious that the solution has been only temporary. The ever-increasing exports from the port of Liverpool and the rapid development of Merseyside as an industrial centre have resulted in a great increase in motor traffic through the tunnel. Plans are now being made for the use of the space between the walls supporting the reinforced concrete roadway at the lower level of the tunnel (1840).

The Thames Tunnel

The Thames Tunnelis a tunnel, 35 feet wide and 1,300 feet long, beneath the River Thames in London, between Rotherhithe and Wapping. Originally constructed for pedestrian use, it is currently used by trains of the London Underground's East London Line. It was built by Marc Isambard Brunei and his son Isambard Kingdom Brunei in the 19th century.

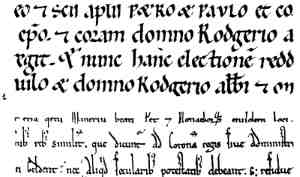

A previous attempt at construction by Richard Trevithick in 1808 failed due to the difficult conditions of the ground. Marc Brunei's approach at the start of the project in January 1825 was to begin by digging a large shaft on the south bank at Rotherhithe. He did this by first building a brick cylinder above ground and then gradually sinking it by removing the earth beneath it. Brunei and Thomas Cochrane devised the tunnelling shield to dig the tunnel. The Illustrated London News of 25 March 1843 described how it worked: "The mode in which this great excavation was accomplished was by means of a powerful apparatus termed a shield, consisting of twelve great frames, lying close to each other like as many volumes on the shelf of a book-case, and divided into three stages or stories, thus presenting 36 chambers of cells, each for one workman, and open to the rear, but closed in the front with moveable boards. The front was placed against the earth to be removed, and the workman, having removed one board, excavated the earth behind it to the depth directed, and placed the board against the new surface exposed. The board was then in advance of the cell, and was kept in its place by props; and having thus proceeded with all the boards, each cell was advanced by two screws, one at its head and the other at its foot, which, resting against the finished brickwork and turned, impelled it forward into the vacant space. The other set of divisions then advanced. As the miners worked at one end of the cell, so the bricklayers formed at the other the top, sides and bottom. "

The key innovation of the tunnelling shield was its use of compressed air to keep the working face from flooding. But the dangers of compression and decompression were not understood, and workers soon fell ill from the poor conditions, including Brunei himself; ten men died during the project.

Work was slow, progressing at only 8-12 feet a week. Isambard Kingdom Brunei took over as chief engineer, and when on 18 May 1827 the tunnel flooded, he used a diving bell to repair the hole at the bottom of the river. Following the repairs and the drainage of the tunnel, he held a banquet inside it.

The tunnel was flooded again the following year, 12 January 1828, and the project was abandoned for seven years, until Marc Brunei succeeded in raising sufficient money to continue work. Impeded by further floods and gas leaks (methane and hydrogen sulphide), it was not completed until 1842. It was finally opened to the public on 25 March 1843. The tunnel was not, however, a financial success and soon acquired an unpleasant reputation.

In 1865 the tunnel was bought by the East London Railway Company and was adapted for trains, which ran out of Liverpool Street station.

It was subsequently absorbed into the London Underground. In 1995 it became the focus of considerable controversy when the tunnel was closed for long-term maintenance, with the intention of sealing it against leaks by "shotcreting" it.

This led to a legal conflict with architectural interests wishing to preserve the tunnel's appearance and disputing the need for the treatment. Following an agreement to leave a short section at one end of the tunnel untreated, and more sympathetic treatment of the rest of the tunnel, the work went ahead and the route reopened - much later than originally anticipated - in 1998.

Although the tunnel itself cannot usually be visited (except by train), the engine house on the southern bank, which originally housed the pumps to drain the tunnel, has been restored and converted into a museum.

Дата добавления: 2016-08-23; просмотров: 1673;