Britain’s Roman villas

Numerous monuments recall the 400 or so years (from A.D. 43 to the beginning of the fifth century) when Britain was part of the Roman Empire. Ancient city walls, including fragments to the ones that once defended London and Colchester, old roads like the Fosse Way and Watling Street. The frontier defenses of Hadrian’s Wall. The bastions at Portchester. An arched gateway at Lincoln. Bath’s great bath. The theatre at Verulamium, near St. Albans. But it is at the villas that one feels closest to the everyday life of Roman Britain.

Some of the villas were small farms. Others were great houses. They were well built, usually of one storey, and handsomely decorated. Often they had large courtyards and spacious outbuildings – barns for storage, stables, shelter for pigs and cattle, and living space for the laborers who worked on the estate.

The first villa was built here around A.D. 80 – 90. it was a house of flint and mortar with, beneath ground level, a deep room, used as grain store. The type of owner was a native farmer. Around A.D. 180, however, the villa became the home of a Roman of Mediterranean origin, a man of wealth who greatly extended the house, adding kitchens and baths and turning the deep room into a place of worship, decorated with a fresco painting of water goddesses, part of which survived.

The eventual fate of most of the Roman villas of Britain remains uncertain. But it is known that Lullingstone was destroyed by fire early in the fifth century. Afterwards the hill-wash crept in form the downs and covered the ruins, keeping them hidden for hundreds of years until the middle of the 18th century, when excavations for a deer fence revealed part of a mosaic floor. No further investigation took place at the time, and it was not until 1949 that systematic excavation of the site began.

In a similarly accidental way clues to the presence of the villas at Rudston, Yorkshire, at Bignor, Sussex, and at Chedworth in Gloucestershire were discovered.

The Roman Twilight

The destruction of the Roman Empire was due to a unique combination of internal and external causes.

For long the Empire persisted rather because of the absence of any outside force powerful enough to attack it than from its own strength. In the fourth century A.D. a serious of westward migratory movements across the steppes of Asia and Europe forced the Germanic tribes nearest to the Roman frontiers into motion. At its heart we can trace the westward migration of the Huns, Mongol tribes from Central Asia. At first these Germanic tribes were allowed and even encouraged to enter the Empire, where they were absorbed and partially Romanized. Gradually the hold of the central government on outlying provinces was relinquished and one by one they were overrun by barbarian tribes who set up independent kingdoms of varying character – some largely Roman in culture and language, others almost wholly barbarian.

Britain, as the most remote and among the most exposed of the provinces, was among the earliest to fall away and lost most completely its Roman character.

In 407 two events ended the long period of Roman occupation. One was the departure of Constantine, with the bulk of the troops stationed in Britain, in an attempt to secure the Imperial purple. The other was the crossing of the Rhine into Gaul of a host of Germanic tribesmen who cut Britain off from the Roman world and prevented the return or replacement of the departed legions. The people of South and East Britain were left to improvise their own government and defense against their never conquered kinsmen of the more parts of the islands.

The Names “England” and “English”

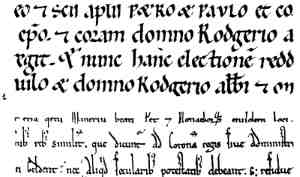

The Celts called their Germanic conquerors “Saxons” indiscriminately, probably because they had had their contact with the Teutons through the Saxon raids on the coast. Early Latin writers, following Celtic usage, generally call the Teutons in England “Saxones” and the land “Saxonia”. But soon the terms “Angli” and “Anglia” occur beside “Saxones” and refer not only to the Angles individually but to the Teutons generally. Æthelbert , king of Kent, is styled “rex Anglorum” by Pope Gregory in 601, and a century later Bede called his history the “Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum” . in time “Anglia” became the usual terms in Latin texts. From the beginning, however writers in the vernacular never call their language anything but Englisc (English). The word is derived from the name of the Angles ( O.E.Ængles) but is used without distinction for the language of all the invading tribes. In the like manner the land and its people are early called “Anglekynn” (Angle kin or race of the Angles), and this is the common name until after Danish period. From about the year 1000 “Englaland” (Land of Angles) begins to take its place. The name “English” is thus older than the name “England”. It is not easy to say why England should have taken its name from the Angles. Possibly a desire to avoid confusion with the Saxons who remained on the Continent and the early supremacy of the Anglian kingdoms were the predominant factors in determining usage.

Дата добавления: 2016-07-27; просмотров: 4365;